In-Orbit Servicing (IOS) refers to extending the life or functionalities of spacecraft that are already in orbit. This can be done by performing maintenance, adjusting a spacecraft’s orbit, changing the direction it is facing, providing more fuel, or even changing or upgrading the instruments onboard.

There are a number of technologies being developed for in-orbit servicing of GEO satellites. These include:

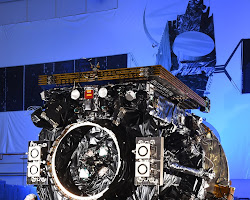

- Robotic arms: Robotic arms are being developed that can be used to grapple and manipulate satellites in orbit. These arms can be used to perform a variety of tasks, such as refueling, repairing, and upgrading satellites.

- Automated docking systems: Automated docking systems are being developed that can be used to dock two satellites together in orbit. These systems can be used to transfer supplies, personnel, or equipment between satellites.

- On-board sensors: On-board sensors are being developed that can be used to monitor the health of satellites in orbit. These sensors can detect problems with satellites before they fail, and can also be used to guide robotic arms and docking systems.

The economics of in-orbit servicing of GEO satellites are still being developed. However, there are a number of potential benefits to this technology, including:

- Reduced costs: In-orbit servicing can reduce the cost of launching new satellites by extending the life of existing satellites.

- Improved performance: In-orbit servicing can improve the performance of existing satellites by upgrading their payloads or components.

- Increased flexibility: In-orbit servicing can increase the flexibility of satellite operators by allowing them to customize their satellites to meet changing needs.

The challenges to in-orbit servicing of GEO satellites include:

- The high cost of development and deployment: The development and deployment of in-orbit servicing technology is very expensive.

- The complexity of the operations: In-orbit servicing operations are very complex and require a high degree of precision.

- The risk of failure: The risk of failure is high for in-orbit servicing operations. If a servicing operation fails, it could damage or destroy the satellite being serviced.

Despite the challenges, there is a growing interest in in-orbit servicing of GEO satellites. The potential benefits of this technology are significant, and the costs are expected to come down as the technology matures. As a result, in-orbit servicing is likely to become an increasingly important part of the future of satellite operations.

There are a number of agencies and companies that are developing and deploying in-orbit servicing solutions. Some of the most active players in this space include:

- SpaceLogistics: SpaceLogistics is a subsidiary of

Northrop Grumman that is developing a robotic servicing vehicle (RSV)

called the Mission Extension Vehicle (MEV). The MEV has been used to

extend the life of two geostationary satellites, Intelsat 901 and

Eutelsat 172B.

- Northrop Grumman: Northrop Grumman is also

developing a satellite servicing system called the Space Infrastructure

Servicing (SIS) vehicle. The SIS vehicle is designed to refuel, repair,

and upgrade satellites in geostationary orbit.

- MDA: MDA is a Canadian company that is developing a

satellite servicing system called the Robotic Orbital Servicing Vehicle

(ROSV). The ROSV is designed to refuel, repair, and upgrade satellites

in geostationary orbit.

- Kepler Space Technologies: Kepler Space

Technologies is a company that is developing a satellite servicing

system called the Kepler ACES. The Kepler ACES is designed to refuel,

repair, and upgrade satellites in low Earth orbit.

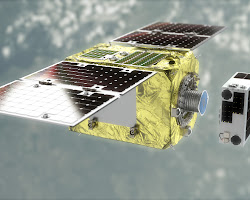

- Astroscale: Astroscale is a Japanese company that

is developing a satellite servicing system called the RemoveDEBRIS. The

RemoveDEBRIS is designed to remove space debris from orbit.

These are just a few of the agencies and companies that are developing and deploying in-orbit servicing solutions. As the technology matures, it is likely that more players will enter this market.

In addition to these companies, there are also a number of government agencies that are involved in the development of in-orbit servicing solutions. These agencies include:

- NASA: NASA is developing a number of in-orbit

servicing technologies, including the Restore-L mission, which will

refuel the Landsat 7 satellite.

- ESA: ESA is developing a number of in-orbit

servicing technologies, including the CleanSpace-1 mission, which will

demonstrate the ability to capture and deorbit a small satellite.

ESA Moves Ahead With In-orbit Servicing Missions: Isn’t it strange that when satellites run out of fuel or a single component breaks down, we just discard them? ESA and European industry have joined forces to make sure that our satellites can live on. ESA has conducted extensive work on IOS, including as part of its Clean Space initiative for the removal and prevention of space debris. As part of this research, ESA Preparation invited industry partners to outline their vision of Europe’s first IOS mission, to be launched as early as 2028.

Astroscale, ClearSpace, D-Orbit and Telespazio (collaborating with Thales Alenia Space) were given funding to mature their ideas, and their results were presented in preparation for the 2022 ESA Council at Ministerial level.

“In-Orbit Servicing could fundamentally change the way that future satellites are designed and operated. Towards the 2030s, satellites will likely need to be designed with interfaces and other features that allow service and disposal spacecraft to do their work,” says Ross Findlay, IOS system engineer at ESA.

Satellites of the future may carry less fuel and larger instruments. The option of in-orbit assembly also means that future satellites could be designed to consist of modules that are easy to assemble and individually replace. For the same reasons that plugs and sockets for electronics have standard shapes, discussions on standardised ‘docking’ structures have already begun, to make it easier for one model of servicing spacecraft to latch on to different types of satellites.

In-Orbit Servicing is a commercial question

More than half of all satellites being launched are commercial, so

commercial operators need to be involved if we wish to make servicing a

standard procedure. “We made it a mandatory endpoint for all four teams

to have some kind of relationship to an actual customer that they want

to provide this service to,” notes Ross.

“This led to very interesting discussions between ESA, the companies interested in setting up IOS missions, and companies who own the satellites to be serviced. Take for example the legal implications: if two satellites collide during servicing, who is responsible?”

The Preparation element of ESA’s Basic Activities was in a unique position to support these mission assessment studies, including the bigger-picture commercialisation opportunities. “These activities, and their contribution to the Ministerial Council meeting, demonstrates the importance of the Preparation programme in supporting ideas to become a reality,” says ESA Discovery & Preparation officer Moritz Fontaine.

Telecommunications industry wants life-extension services

The four selected companies investigated the opportunities for IOS

operations for satellites in low-Earth orbit (LEO) and geostationary

orbit (GEO). LEO hosts important satellites such as the Hubble Space

Telescope, the Copernicus Sentinel Earth observation satellites, and the

International Space Station. GEO hosts Europe’s series of Meteosat

weather satellites and, importantly, most satellites used for

telecommunications.

A clear outcome from the four studies is that the telecommunications industry is keen for life extension services to be up and running as soon as possible. Particularly relevant is orbital maintenance: operators have to make sure the spacecraft stays exactly where it should be, and change the orbit or rotation if it has drifted over time.

Doing so costs fuel. The proposals detail how a servicing spacecraft can latch on to satellites that have run out of fuel and perform the necessary orbit control. The servicing spacecraft can stay attached for as long as needed, after which it parks the satellite in a so-called ‘graveyard orbit’ and moves on to the next satellite that needs servicing.

Fresh eyes from New Space

Interestingly, three of the four proposals came from what you might call

‘New Space’ companies. “These are newer actors with perhaps slightly

different ways of approaching design and development, often involving

smaller teams and more fast-paced iterations. It was refreshing to

compare different workflows and discuss possible forms of

collaboration,” says Ross.

Following these four studies funded by ESA Preparation, ESA’s Space Safety programme has decided to move forward with two of the proposed missions. The programme envisions that IOS operations will continue to expand, both in number of missions and their capabilities. European industry has the ambition to make IOS common procedure by the early to mid-2030s.

- JAXA: JAXA is developing a number of in-orbit

servicing technologies, including the HTV-X mission, which will

demonstrate the ability to refuel and repair a satellite in orbit.

The development and deployment of in-orbit servicing solutions is a complex and challenging task. However, the potential benefits of this technology are significant, and it is likely to play an increasingly important role in the future of space operations.

No comments:

Post a Comment