|

The security of subsea cables: an enduring naval challenge - Maritime Foundation |

1. The DSR is part of China's larger Belt and Road Initiative, providing digital infrastructure and technology to developing countries.

2. It covers areas like telecommunications networks, AI, cloud computing, e-commerce, surveillance tech, and smart cities.

3. China has signed DSR agreements with at least 16 countries, but the actual number is likely much higher.

4. Benefits for recipient countries include:

- - Filling critical infrastructure gaps

- - Providing affordable, high-quality technology

- - Facilitating economic growth

- - Knowledge transfer and training programs

- - Potential for China to export its model of tech-enabled authoritarianism

- - Risk of surveillance and control capabilities being misused

- - Cybersecurity and espionage risks from Chinese-built infrastructure

- - Acceleration of internet fragmentation

7. Demand has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

8. Some developing countries are starting to express concerns about sovereignty and debt related to DSR projects.

9. China has already spent an estimated $79 billion on DSR projects and plans to expand significantly.

10. The initiative is likely to be a source of ongoing geopolitical tension between China and countries concerned about its implications.

The DSR represents a major expansion of China's global digital influence, offering significant benefits to recipient countries but also raising complex security and governance challenges.

Securing the Digital Seabed: Countering China’s Underwater Ambitions

Air University (AU) > Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs

Abstract

China’s Digital Silk Road provides Beijing with a potent instrument to disrupt undersea cables and gain an advantage in the Indo-Pacific. Submarine fiber-optic cables are critical infrastructure yet vulnerable to sabotage. This paper examines how the planned Pakistan and East Africa Connecting Europe (PEACE) cable from China could become a new flashpoint in the Western Indian Ocean. The cable has strategic implications, allowing China to project power and leverage its technological edge. Its landing sites in Pakistan and Djibouti would anchor Chinese naval assets in key chokepoints. The civil-military fusion strategy also facilitates surveillance and espionage via the cables. To counter such threats, India and allies must secure submarine cables through monitoring, contingency planning, and multilateral cooperation. Investing in alternative “democratic digital networks” can also mitigate China’s ambitions. Ultimately, submarine cables are emerging as a domain of geopolitical competition requiring policies that safeguard their resilience.

***

The Indian Ocean is becoming a major theater of geopolitical contest for strategic dominance in the wider Indo-Pacific. The Western Indian Ocean (WIO), in particular, has emerged as the strategic center stage for great-power games. This region comprises the Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea, Red Sea, and critical straits of Bab-el-Mandeb, Hormuz, and Suez Canal. It is the key entry point for major powers and plays a vital role in geostrategic calculations given its transit route significance for trade, energy security, and submarine data cables. The WIO’s cables are intricately linked to Indo-Pacific geopolitical dynamics and rivalries among regional nations. As the hub connecting Europe, Asia, and Africa, the WIO’s critical technology infrastructure for undersea data cables is essential in shaping power dynamics. The evolving security dynamics necessitate examining cable protection and security as an ongoing interest. This article highlights Indian and global efforts to secure critical technologies infrastructure as national security strategy. It examines cable geosecurity dynamics in the WIO’s “great game” and India’s counterstrategies to contain China’s technology push for geopolitical gains.

Submarine Data Cables

Submarine cables and pipelines constitute critical infrastructure for transporting energy (including gas, oil, and electricity) and telecommunications. Submarine data cables, defined as “means of communication laid on the seabed between two terminal points,”[1] can be categorized into two types: power cables, responsible for transmitting energy, and data cables, facilitating the transmission of Internet, voice, and data.[2] In the realm of promoting telecommunications and international communications, the concept of freedom of the seas takes center stage, with the installation of underwater data cables emerging as a pivotal component. These submarine data cables are strategically placed on the ocean floor, connecting land-based stations, and play a vital role in carrying voice and data traffic worldwide, serving multiple purposes.

In the modern era, these data cables have become the linchpin of the global economy and a cornerstone of national security strategy. The growing dependence of societies on the Internet for daily life underscores the necessity for a comprehensive understanding of the framework underpinning the security of these critical electronic communication systems. Presently, fiber-optic cable-based systems are increasingly preferred for day-to-day data transmission, offering not only cost-efficiency but also significantly faster data and voice transfer compared to satellite alternatives. Their applications extend to various domains, encompassing marine scientific data collection, underwater oceanographic research, digital mapping of oil and gas exploration sites, among others. [3]

The Information and Communication Technology Revolution and Modern-day Conflict

The information and communication technology (ICT) revolution, post–Cold War, has assumed a role that can potentially exacerbate modern-day conflicts. The concept of hybrid warfare, characterized by the smart and innovative utilization of advanced technologies, has gained prominence. Historically, the control of information and communication systems has been leveraged for political and strategic gains, involving disinformation campaigns, propaganda, and other manipulative tactics to influence political landscapes and even topple governments. In the contemporary context, the widespread reach of ICT has amplified the capacity of malevolent actors and states to sway larger populations to serve their vested interests.[4]

The notion of hybrid warfare has gained substantial traction, particularly following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Ongoing uncertainties surrounding projects like the Nord Stream and Nord Stream 2, involving multi-billion-dollar natural gas pipelines through the Baltic Sea, have fueled conspiracy theories regarding the vulnerability of undersea critical infrastructure. This infrastructure is seen as potential attack sites for malevolent actors seeking to exploit vulnerabilities in nation-states related to energy, power, and information.[5]

The Significance of Submarine Data Cables

In today’s interconnected world, the Internet and e-communications rely heavily on submarine data cables. These undersea cables facilitate the transmission of vast amounts of data, Internet traffic, and voice across oceans and nations, serving as the backbone of the contemporary global landscape.[6] The inception of long-distance undersea cable communication dates to the nineteenth century when the first undersea data cable, used for telegraphy, was laid in 1850. This copper-based telegraph wire connected the United Kingdom and France beneath the English Channel. Subsequently, the first successful transatlantic cable was established in 1866, marking significant milestones in long-distance communication technology.[7]

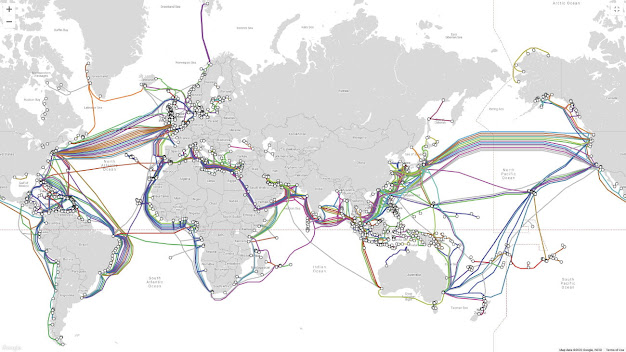

The evolution of undersea cables has seen them become more advanced and extensive, spanning over a million kilometers across the ocean floor, linking continents, islands, and nation-states. In today’s world characterized by “complex interdependence,” submarine data cables have emerged as one of the most critical infrastructures, raising concerns about potential anthropogenic and natural threats that could disrupt communication networks, thereby impacting economies ranging from single states to entire continents. Consequently, there is a pressing need for a comprehensive evaluation of the governance architecture governing the laying, protection, and security of these vital undersea data cable infrastructures.

Authoritarian Regimes and Control over Data Cables

Information and communication pathways are pivotal for the global community, often described as a “powerful tool, for liberation or repression, depending on who controls it.”[8] In this context, it is imperative to examine the role of authoritarian regimes such as the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in exerting overarching control over the undersea data cable industry. This control is pursued through a civil-military fusion strategy, where the civil sector collaborates with the military sector to realize the Chinese dream of “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” by 2049.

The PRC’s Digital Silk Road (DSR), announced in 2015 as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), underscores the clear linkage between digital connectivity and Beijing’s geopolitical and geostrategic ambitions of establishing a Sino-centric global order. To this end, the PRC is making substantial investments through both private and state-owned firms in the submarine data cable sector and its supporting infrastructure. The civil-military fusion approach facilitates the global expansion of these companies while aligning them with China’s grand geopolitical objectives. A pertinent example discussed in this paper is the planned Pakistan and East Africa Connecting Europe (PEACE) submarine data cable project by the PRC, which holds the potential to become a significant geopolitical flashpoint in the WIO region. The strategic advantage gained by the PRC in the region could have far-reaching implications for regional security architecture, a matter of critical concern for India and its interests.

Securitization of Submarine Data Cables

India and the world rely heavily on the intricate network of submarine cables crisscrossing the seabed. These cables serve as strategic communication chokepoints in the global information highway, rendering them critical assets for global security. Responsible for carrying nearly 97 percent of worldwide Internet traffic, these submarine cables represent a tangible form of transnational connectivity that remains inadequately explored within the global geopolitical and geosecurity discourse.[9] The absence of a clearly defined international governance framework has given rise to security concerns, rendering these cables susceptible to sabotage and espionage, both in times of peace and war. These cables can grant nation-states a significant geopolitical and geostrategic advantage in international affairs. As of 2023, approximately 529 cable systems (totaling approximately 1.3 million kilometers in length) and 1,444 landing stations are operational or under construction.[10]

Submarine cables stand out as the swiftest, most cost-effective, and reliable means for global data transmission. In an era where the world’s reliance on digital technology encompasses civilian communication, commerce, agriculture, healthcare, military logistics, and financial transactions, these subaquatic cables encased in steel and plastic have become indispensable to national security. Any disruption to these cables could paralyze the affected region and push the world to the brink of a ‘new great depression.’[11] An illustrative incident occurred in January 2022 when a volcanic eruption severed the sole fiber-optic cable connecting Tonga to the rest of the world—the Tonga Cable to Fiji. This event left Tonga in a state of information isolation, resulting in severe economic losses and hindering the prompt and effective coordination of international humanitarian assistance. This episode underscored the heightened security imperative surrounding these cables, which are pivotal for global connectivity.[12]

Viewed from the perspective that nearly all governments worldwide utilize these cables to facilitate external and domestic communication, the significance of submarine cables in diplomacy, military communications, and trade and commerce cannot be overstated. These cables facilitate the transmission of transactions worth up to 10 trillion USD per day, primarily through private entities, as government-owned satellite usage for classified data remains limited. Consequently, the heavy reliance on these critical infrastructure components by government and military agencies can have catastrophic repercussions on a state’s security and its ability to respond to emerging threats. A case in point is the 2008 incident when a submarine cable between Egypt and Italy ruptured, resulting in a substantial decline in US unmanned drone flights to Iraq.[13] Thus, the question of ownership, construction, operation, and control of these critical infrastructures has become more relevant than ever before.

The private sector holds a monopoly over the planning, production, deployment, and maintenance of these submarine cables. Presently, SubCom of the United States of America, Alcatel Submarine Network of France, NEC of Japan, and Huawei Marine Networks of China rank as the four largest suppliers, owners, and builders of submarine cables globally.[14] China’s share in the global submarine cable sector rose to 11.4 percent in 2019, with China now aiming to expand its share to 20 percent between 2025 and 2030.[15]

Recently, the critical nature of the submarine cable communication network has come to the fore in the security considerations of the Western strategic community. Concerns have arisen about Russia potentially leveraging these undersea cables to disrupt their communication linkages with the world, thereby crippling their economies and other facets of daily life in retaliation for their support to Ukraine in the ongoing conflict. Heightened concerns stem from increased Russian submarine activity in proximity to these undersea cables. Britain’s Admiral Tony Radakin remarked, “Undersea cables that transmit Internet data are ‘the world’s real information system,’ and added that any attempt to damage them could be considered an ‘act of war.’”[16] Consequently, the possibility of submarine cable sabotage in times of peace or conflict has accentuated vulnerabilities, risk factors, and disruption indicators within the global submarine cable network and supporting infrastructure, including the undersea cables in the WIO.

Against the backdrop of the escalating technological rivalry between India and China, especially in the realms of espionage and data acquisition, it becomes imperative to acknowledge the pervasive role of submarine cables in these intensifying geopolitical frictions. China’s DSR strategy emerges as a potent instrument that could be wielded to potentially disrupt, sabotage, or clandestinely gather intelligence from undersea cables. These cables serve as the linchpin of global communication networks and are critical to the strategic interests of both nations. Deliberate manipulation or compromise of undersea cables could provide China with a distinct geopolitical advantage in the ongoing competition or future conflicts with India in the region.

Digital Silk Road: China’s Underwater Expansion and Digital Warfare Strategy

Announced in 2015 as a digital component of the BRI, the PRC’s DSR plan aims to construct a Sino-centric digital infrastructure. Its objectives include exporting Beijing’s digital capabilities, promoting Chinese technology businesses, and gaining access to vast data repositories. The PRC envisions the DSR expanding its digital influence across the wider Indo-Pacific region by investing in critical information and digital infrastructure, including undersea cables, fiber-optic networks, fifth-generation (5G) networks, and data centers abroad.[17]

Consequently, there has been a notable increase in Beijing’s engagement with African, Latin American, and West Asian states, particularly in digital infrastructure development. This engagement presents significant opportunities. As a subset of the BRI, the DSR strategically supports the PRC’s aspiration for national rejuvenation by 2049. It achieves this through financing, constructing, and developing infrastructure in Indo-Pacific countries. A prime example is the extensive involvement of Chinese multinational corporation (MNC) Huawei in the development of critical information infrastructure across many African nations, with particular attention drawn to the "Safe Cities" program. Analysts have raised concerns, suspecting Beijing of employing its MNCs as state agents to surveil and exert authoritarian control over digital information flow to serve the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) interests in resource-rich African regions.[18]

More than 150 countries have signed cooperation agreements related to China’s BRI.[19] Beijing intends to employ the DSR as a potent instrument to advance its expansionist policies and employ economic coercion through a skillfully designed civil-military fusion strategy.

China continues to enhance its unconventional capabilities to gain an advantage in the digital warfare landscape. The CCP invests in modernizing the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy, enabling it to expand naval assets underwater. This expansion is aimed at effectively disrupting adversary communication lines in digital warfare. China’s preparations are oriented toward asymmetric conflict, focusing on operating in "gray zones" rather than engaging in full-scale wars. [20] This digital warfare strategy promises substantial results with minimal investment in resources.

In this context, Beijing’s DSR seeks to establish a Sino-centric global digital order by expanding and exporting Chinese technology through state-controlled and private corporations.[21] This strategy grants the PRC access to extensive data repositories. In 1999, the PRC introduced its ’Go Out’ or ’Going Global’ strategy, incentivizing state-owned and private corporations to invest and expand globally.[22] Beijing provided incentives and subsidized loans to technology firms to expand to strategic regions worldwide.[23] Additionally, China enacted multiple laws mandating Chinese firms to “support, assist, and cooperate in government’s intelligence and national security efforts.”[24]

One such law is the National Intelligence Law of 2017, obligating all organizations and citizens to cooperate with state intelligence work and maintain the secrecy of national intelligence work. This grants the CCP extraordinary powers to engage in sabotage, espionage, hacking, and surveillance of an adversary’s communication networks, enabling the collection of sensitive economic, diplomatic, and military information required to pursue its strategic goals.[25] This threat to US communication networks was acknowledged in the 2019 Worldwide Threat Assessment report, where the Director of National Intelligence warned that “China presents a persistent cyber-espionage threat and a growing attack threat to our core military and critical infrastructure systems.”[26]

With the planned PEACE submarine cable becoming operational, China’s expansion in undersea infrastructure and digital authoritarianism will receive a significant boost. The CCP harnesses cutting-edge communications technology to strengthen its control domestically and expand its influence abroad. The PEACE cable, privately owned and invested in by Peace Cable International Network Co., Limited (a subsidiary of China’s HENGTONG Group) and supplied by HMN Tech (formerly Huawei Marine Networks), will grant China a vital advantage in the region.[27] The project comprises three segments. Initially, a submarine cable will extend from Pakistan to France, passing through the Red Sea and Suez Canal, ultimately landing in France. Another branch of the PEACE cable will traverse Eastern Africa, connecting Kenya and Seychelles, and continue to the Maldives before finally reaching Singapore. The third and final leg of the PEACE cable will stretch toward South Africa, providing connectivity to the Southern African Development Community (SADC), East Africa, West Asia, and Europe, thus expanding the Chinese digital footprint. This strategic expansion positions China to assert itself both geopolitically and geoeconomically, potentially challenging the dominance of the United States and India in the region.

China currently possesses key infrastructure assets in areas of significant geopolitical importance, including the port of Gwadar, Pakistan, operated by China Overseas Ports Holding Company; Djibouti (China’s first overseas military base); and Egypt (Beijing’s largest trading partner in the region). These assets are strategically vital to Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions, as they facilitate its trade and energy imports through key chokepoints adjoining these states. Thus, China and Huawei, the project implementer, have strategically selected nations of significant geostrategic importance as intermediary locations to further their objectives and strategic activities.

Fig 1. PEACE: A 1,500-km-long network connecting Asia, Africa, and Europe. (Source: Peace Cable International Network Co., Limited http://www.peacecable.net/.)

With the PEACE cable, China establishes a permanent presence in the strategic chokepoints of these critical infrastructures. Landing stations in Pakistan and Djibouti provide the PLA Navy with a strategic advantage, enabling permanent stationing in the WIO region and facilitating the collection of strategic information for both above and undersea operations in these key chokepoints. Chinese investments in digital infrastructure, fiber-optic cables, business partnerships, and technical expertise within these pivotal nations will amplify Beijing’s influence as these economies transition to digital platforms. China’s growing economic and soft-power influence, driven by infrastructure and digital initiatives, has the potential to displace India from its traditionally dominant position in its extended maritime neighborhood. As Beijing shifts its focus to the WIO and the wider Indo-Pacific, countries like Pakistan, Djibouti, and Egypt, with their significant digital intersections and vital water passages, may increasingly align with China’s sphere of influence. Submarine cables landing in mainland China or facilities financed by China’s BRI loans grant the PRC the leverage to conduct extensive geopolitical propaganda campaigns, aiming to deny opponents the strategic advantage of space and technology in ongoing great-power competition.

Figure 2. Undersea cable chokepoints affecting Asia and the Middle East. (Source: “Arctic Submarine Fiber-optic Cable Line Polar Express,” Morsviazsputnik (website), 2020, https://www.marsat.ru/.)

The Security Challenge: Sabotage and Espionage

Submarine cables represent critical infrastructure susceptible to sabotage and espionage, including physical damage. Any disruption of these cables could have devastating global repercussions. Sabotaging these cables can be viewed as a strategic maneuver to weaken an adversary prior to the outbreak of kinetic warfare.[28] States or state-sponsored nonstate actors often employ specially equipped submarines and techniques to tap or completely sever undersea cables, as exemplified in 2013 when three individuals equipped with specialized scuba gear and fishing boats attempted to cut the SEA-ME-WE 4 undersea cable. This incident disrupted communication traffic between Europe and Egypt, underscoring the vulnerability of these vital assets.[29]

Another critical infrastructure at risk of sabotage is the cable landing stations, where undersea cables connect to terrestrial digital communication networks. The convergence of multiple cables at these stations makes them prime targets during conflicts. Additionally, natural threats like shark attacks, earthquakes, and tsunamis pose a risk of disruption. However, what concerns the strategic community most is the deliberate threat to these crucial assets. Chinese fishing fleets, under the guise of human error, could intentionally damage these cables, or specialized units of the PLA Navy might undertake missions to disrupt communication flow.

Recent events have underscored the potential for undersea cables to become embroiled in conflicts involving China and Taiwan. In February 2023, Chinese maritime vessels severed two communication cables linking Taiwan with its Matsu islands, causing Internet connectivity disruptions for the island’s residents. The "unintended" targeting of these cables near China’s coast could be interpreted as a calculated maneuver to demonstrate China’s capability to disrupt communication and potentially isolate Taiwan.[30] These incidents highlight the significance of undersea cables as tools for leveraging power in modern conflicts.

In contrast, espionage does not necessarily entail damage or disruption to undersea cables but is executed covertly to gain access to data flowing through these cables, either underwater or at designated landing or data centers. This requires specialized training and techniques. The PLA’s Science and Engineering University provides tailored training in advanced digital warfare and research related to defense technology and military equipment.[31] China is rapidly closing the gap with the US and Russia in this domain. Russia, for instance, possesses the AGS, a small nuclear-powered minisubmarine capable of tapping fiber-optic cables in challenging underwater environments.[32] The United States has also conducted cable-tapping operations, notably during the Cold War when the submarine USS Halibut intercepted sensitive information from a military cable passing through the Sea of Okhotsk to the Kamchatka Peninsula in the eastern Soviet Union. This operation, codenamed Ivy Bells, continued for a decade and utilized three specially modified submarines.[33] The ability to tap and gather intelligence provides significant advantages to a nation’s military. Tactics of sabotage and espionage can be employed simultaneously, as demonstrated by Britain during World War I when it severed most of Germany’s undersea telegraph networks, leaving one cable intact, which was subsequently tapped to gather vital intelligence during the war.[34]

The DSR is envisioned as a response to unconventional warfare, providing the PLA with command and control over the world’s strategic communication gateways. Investments in these infrastructures aim to furnish the PRC with intelligence, military battlefield information, and geopolitical advantages far beyond its strike zones. The digital database enhances the PLA’s operational flexibility and responsiveness in both conventional and unconventional warfare scenarios. The PLA regards digital warfare as an integral component of modern warfare, with an emphasis on “suppressing, degrading, disrupting, or deceiving enemy electronic equipment.”[35] The US Department of Defense 2020 Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China clearly states that:

China has publicly identified cyberspace as a critical domain for national security and declared its intent to expedite the development of its cyber forces. The PRC presents significant, persistent cyber espionage and attack threats to military and critical infrastructure systems. China seeks to create disruptive and destructive effects—from denial-of-service attacks to physical disruptions of critical infrastructure—to shape decision-making and disrupt military operations in the initial stages of a conflict by targeting and exploiting perceived weaknesses of militarily superior adversaries. . . . Authoritative PLA sources call for the coordinated employment of space, cyber, and electronic warfare (EW) as strategic weapons to “paralyze the enemy’s operational system of systems” and “sabotage the enemy’s war command system of systems” early in a conflict. Increasingly, the PLA considers cyber capabilities a critical component in its overall integrated strategic deterrence posture, alongside space and nuclear deterrence.[36]

Strategic Response and India’s Options

This article considers a matrix of potential strategic responses, taking into account the implications of the DSR on the geopolitical and geosecurity landscape in India’s extended maritime neighborhood. The absence of a singular or coordinated strategy for governing and securing submarine cables demands immediate attention. India possesses unrivaled demographic, economic, and geographical advantages, positioning New Delhi to emerge as a prominent global player in submarine cable networks. However, capitalizing on this substantial potential necessitates the Indian government’s establishment of policies and regulations that foster investment, aligning with its rapidly growing digital economy.

Assuming the pivotal role of a global and regional hub for submarine data cable networks, India can serve as a strategic countermeasure to China’s ambitions and enhance its digital prowess on the global stage. To achieve comprehensive and holistic security for undersea data cable systems, a combination of operational strategies and a robust safeguarding approach is imperative. This approach encompasses offshore patrolling, the establishment of cable protection zones, and the implementation of a well-defined security audit framework to counteract digital warfare threats.

As India rapidly grows its digital economy, it has compelling reasons to maintain vigilance regarding potential threats to undersea cables. Recognizing the vital importance of safeguarding its national prosperity and security, India should contemplate adopting innovative policy solutions reminiscent of the cable protection zones (CPZ) established by Australia and New Zealand. These CPZs would delineate restricted areas within India’s sovereign waters, where activities such as anchoring, bottom trawling, and specific types of fishing would face prohibitions to prevent cable damage. To ensure compliance, India could impose substantial fines on violators, mirroring the stringent framework outlined in Australia’s Telecommunications Act of 1997.[37] Furthermore, ships operating within these zones should be mandated to transmit their positions to the Indian Coast Guard for continuous monitoring, utilizing coastal radar, surveillance aircraft, unmanned aerial vehicles, and surface patrols.

Steps taken, such as the creation of the tri-service Cyber Defense Agency in 2018 and the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) recommendations on Licensing Framework and Regulatory Mechanism for Submarine Cable Landing in India, demonstrate India’s commitment in the right direction.[38] The recent TRAI legislation, which proposes designating undersea cables as critical information infrastructure eligible for protection by the National Critical Information Infrastructure Protection Centre (NCIIPC), enhances their security and shields against potential cyberthreats, strengthening their safeguarding. Nevertheless, addressing this transnational security challenge calls for a more comprehensive response.

Like-minded nation-states should collaborate to provide a democratic digital network alternative to China’s autocratic offerings. Initiatives by the Quad group of countries, including India, Japan, Australia, and the United States, alongside other like-minded powers such as the European Union, should aim to challenge China’s dominant position in this technological domain. Positive steps in this direction are already evident, with efforts to develop regulatory frameworks for the subsea cable market and the formation of the Working Group on Critical and Emerging Technologies showcasing intent to collaborate in this strategic field.[39]

The Quad Partnership for Cable Connectivity and Resilience, with a focus on enhancing Indo-Pacific cable systems through the expertise of Quad nations, prioritizes regional infrastructure and represents a welcome decision. Its aim is to unite public and private sector stakeholders to rectify infrastructure deficiencies and synchronize future advancements, a mission that will assume a pivotal role in forging a democratic and open communication route for the Indo-Pacific region and beyond, thereby ensuring heightened connectivity and resilience. Initiatives like Australia’s Indo-Pacific Cable Connectivity and Resilience Program and the United States’ offer of assistance through the CABLES program are likely to yield positive results in containing China’s expansionism in the digital domain.[40]

To ensure the robust protection and sustained growth of undersea cable infrastructure in the WIO and beyond, New Delhi must harness India’s rapidly expanding digital economy, its strategic location as a global connectivity hub, its abundant technical expertise in the tech industry, its rising global influence, and ongoing efforts to expand connectivity. In this context, the launch of the transcontinental and transoceanic India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) during the recently concluded G-20 summit in New Delhi represents a bold geo-economic initiative of unprecedented scale since China unveiled its BRI in 2013.[41] The IMEC unites capable partner nations to pool resources, reshape supply chains, production networks, and spheres of influence under the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) initiative, reducing overreliance on China in global trade and critical infrastructure. The corridor encompasses a comprehensive scope, including a rail link, an electricity cable, a hydrogen pipeline, and a high-speed data cable. Unlike the opaque and nontransparent nature of the BRI, the IMEC prioritizes viability and draws funding from multiple sources, particularly through public-private partnerships, fostering a technological ecosystem characterized by resilience, integrity, openness, trust, and security, reinforcing democratic principles and human rights. Through the IMEC, India leverages its strategic position to collaborate with friendly foreign nations, countering China’s influence and offering a democratic alternative to the global community. Together, like-minded countries organize and mobilize to ensure technologies align with, rather than undermine, democratic principles, institutions, and societies.

In the context of undersea cables spanning diverse territorial waters and subject to varying national policies and regulations, the release of the “ASEAN Guidelines for Strengthening Resilience and Repair of Submarine Cables” in 2019 serves as a notable precedent.[42] Drawing inspiration from the ASEAN initiative, India can take a leadership role in advocating for the development of a similar guideline within the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), streamlining and simplifying the permit application process for cable repair. Furthermore, by leveraging the collaborative potential of the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS), India can foster cooperative mechanisms aimed at enhancing the safety and security of submarine cables. The region’s multilateral maritime mechanisms, exemplified by IORA, hold promise in addressing nontraditional security threats, especially in light of recent efforts to address maritime security concerns. IONS, serving as a forum for naval professionals from 35 member states, provides a strategic platform for knowledge exchange and consensus-building on maritime security matters in the Indian Ocean, making it an ideal avenue for collaborative submarine cable protection initiatives.

Additional strategies should involve restricting the transmission of sensitive and critical data through privately owned submarine cables. Moreover, prioritizing national capacity enhancement and investing in military modernization for securing these vital undersea cable networks must take precedence. Regular risk assessments and monitoring of these cable projects should be integrated into states’ defensive and offensive strategies. Hence, it is imperative for India to expedite its efforts in developing and integrating autonomous unmanned systems, particularly unmanned underwater vehicles (UUV), into its naval operations. The delayed construction and procurement of high endurance autonomous underwater vehicles (HEAUV) underscore the urgent need for enhancing undersea domain awareness capabilities. While domestic production is desirable, immediate reliance on UUV imports is critical to bridge the capacity gap. Collaborative endeavors involving private companies, research and development projects, and an inclusive approach that engages all stakeholders will be pivotal in accelerating UUV technology advancement, crucial for underwater warfare. The approved flagship project for extra-large unmanned underwater vehicles (XLUUV) should be vigorously pursued, with the prototype slated for completion by 2025.[43] These XLUUVs, designed for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, antisubmarine, surface, and mine warfare, will significantly enhance India’s underwater domain awareness (UDA) capabilities, aligning with the evolving security landscape of naval operations in the Indian Ocean region.

Given that a significant majority of these cables are owned, operated, and managed by private firms, ensuring the private sector’s commitment to national security becomes an essential aspect of policy planning. Encouraging public-private partnership models in this sector can mitigate risks associated with sabotage and espionage. Equally important is the development of a contingency plan to address disruptions promptly.

Lastly, India should engage with the international community and unite like-minded states to establish a comprehensive international legal framework for securing these critical infrastructures.

Conclusion

As we delve into the depths of the world’s oceans, an inconspicuous yet significant battle for global supremacy is underway. China’s digital warfare strategy is crystallizing through initiatives like the PEACE cable and its establishment of undersea bases for submarine cables in the South China Sea and the East China Sea. The Western and Indian strategic communities are acutely aware of China’s growing capacity and capability to extend its digital dominance across the globe.

The global community’s increasing reliance on China’s technologies has far-reaching implications for geopolitics, economies, and global security. China’s planned PEACE cables are forging deep connections into the East African and West Asian regions, posing threats to national, regional, and global security.

Given the constraints India faces, it becomes imperative to embark on a coordinated effort to develop critical infrastructure that can match China’s potential. The DSR, designed to facilitate China’s ascent to superpower status with unconventional strategies, demands counterstrategies to curtail China’s rise.

In the depths of the undersea world, the stage is set for a battle of digital supremacy. How nations respond to this challenge will shape the future of global information networks and the balance of power in the digital age. The undersea cables, often hidden from view but fundamental to our interconnected world, have become the battleground where the struggle for dominance plays out. ♦

Raghvendra Kumar

Mr. Kumar (ORCID ID: 0000-0002-6872-3681) is an independent researcher and analyst specializing in Indian Ocean geopolitics and maritime affairs. He has recently submitted his doctoral thesis, “China’s Engagement with Western Indian Ocean Island States of Africa: Implications for India,” to the Department of African Studies at the University of Delhi, India. Previously he worked as an associate fellow at the Africa’s Maritime Geostrategies (AMG) Cluster, of the esteemed National Maritime Foundation (NMF), Delhi, enhancing his expertise in maritime geostrategies. Prior to his tenure at the NMF, Mr. Kumar taught undergraduate students at the Department of Political Science, Maharaja Agrasen College, University of Delhi. His areas of interest include but are not limited to Africa in the Indian Ocean, India and China in Indian Ocean geopolitics, maritime security studies, and nontraditional security challenges. He can be reached at raghvendrakumar2007@gmail.com.

Notes

[1] Lionel Carter et al., Submarine Cables and the Oceans: Connecting the World (Cambridge, UK: United Nations Environment Programme, 2009).

[2] Tara Davenport, “The Installation of Submarine Power Cables under UNCLOS: Legal and Policy Issues,” German Yearbook of International Law 56 (2013): 107–48.

[3] Edward J. Malecki and Hu Wei, “A Wired World: The Evolving Geography of Submarine Cables and the Shift to Asia,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 99, no. 2 (2009): 360–82, https://doi.org/; Tara Davenport, “Submarine Communications Cables and Science: A New Frontier in Ocean Governance?,” in Science Technology, and New Challenges to Ocean Law, ed. Harry N. Scheiber and Moon-Sang Kwon (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 209–52; and Emily Waltz, “Offshore Wind May Power the Future,” Scientific American, 20 October 2008, https://www.scientificamerican.com/.

[4] Ofer Fridman, Vitaly Kabernik, James C. Pearce, eds. Hybrid Conflicts and Information Warfare: New Labels, Old Politics (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2018), 1.

[5] “White House Says Blog Post on Nord Stream Explosion ‘Utterly False’,’” Reuters, 8 February 2023, https://www.reuters.com/.

[6] Nicole Starosielski, The Undersea Network (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 1–25.

[7] Jonathan E. Hillman, The Digital Silk Road: China’s Quest to Wire the World and Win the Future (New York: Harper Business, 2021).

[8] Hillman, The Digital Silk Road.

[9] James Dean et al., Threats to Undersea Cable Communications (Washington, DC: Public-Private Analytic Exchange Program, 28 September 2017), https://www.hsdl.org/.

[11] James Rickards, The New Great Depression: Winners and Losers in a Post-Pandemic World (New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2021).

[12] Winston Qiu, “Tonga Cables Cut after Volcanic Eruption, at Least Four Weeks to Restore,” Submarine Cable Networks, 19 January 2022, https://www.submarinenetworks.com/.

[13] Michael Sechrist, “Cyberspace in Deep Water: Protecting Undersea Communications Cables by Creating an International Public-Private Partnership” (policy analysis exercise, Harvard Kennedy School of Government, 23 March 2010), https://www.belfercenter.org/.

[14] Colin Wall and Pierre Morcos, “Invisible and Vital: Undersea Cables and Transatlantic Security,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 11 June 2021, https://www.csis.org/.

[15] Helene Fouquet, “China's 7,500-Mile Undersea Cable to Europe Fuels Internet Feud,” Bloomberg, 4 March 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/.

[16] PA Media, “UK Military Chief Warns of Russian Threat to Vital Undersea Cables,” The Guardian, 8 January 8, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/.

[18] Bulelani Jili, “A Technological Fix: The Adoption of Chinese Public Security Systems,” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 20 January 2023, https://gjia.georgetown.edu/.

[19] Xue Gong, “The Belt and Road Initiative Is Still China’s ‘Gala’ but Without as Much Luster,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 3 March 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/.

[21] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China (2020).

[22] Nargiza Salidjanova, Going Out: An Overview of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment (Washington, DC: U.S.–China Economic & Security Review Commission, 30 March 2011), https://www.uscc.gov/.

[23] Hongying Wang, “A Deeper Look at China’s “Going Out” Policy,” Centre for International Governance Innovation, 8 March 2016, https://www.cigionline.org/; and Salidjanova, Going Out.

[24] National Intelligence Law of the People’s Republic, Art. 7 (adopted 27 June 2017), http://cs.brown.edu/. Also, see other relevant Chinese laws obligating citizens and organizations to assist in “national security” efforts, including laws on Counterespionage (2014), National Security (2015), Counterterrorism (2015), and Cybersecurity (2016).

[25] 4 National Intelligence Law of the People’s Republic, Art. 7.

[26] Statement of Daniel R. Coats, Director of National Intelligence, “Worldwide Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community,” Statement for the Record to the Select Committee on Intelligence, 116th Cong. 5, Sess. 1 (29 January 2019), https://www.dni.gov/.

[28] Jon R. Lindsay and Lucas Kello, “Correspondence: A Cyber Disagreement,” International Security 39, no. 2 (2014): 181–92, https://direct.mit.edu/.

[29] Charles Arthur, “Undersea Internet Cables off Egypt Disrupted as Navy Arrests Three,” The Guardian, 28 March 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/.

[30] Wen Lii, “After Chinese Vessels Cut Matsu Internet Cables, Taiwan Seeks to Improve Its Communications Resilience,” The Diplomat, 15 April 2023, https://thediplomat.com/.

[31] Thomas J. Bickford, “Professional Military Education in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army: A Preliminary Assessment of Problems and Prospects,” in A Poverty of Riches: New Challenges and Opportunities in PLA Research, ed. James C. Mulvenon and Andrew N. D. Yang (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2003), 17, https://www.rand.org/.

[32] H I Sutton, “How Russian Spy Submarines Can Interfere with Undersea Internet Cables,” Forbes, 19 August 2020, https://www.forbes.com/.

[33] Sherry Sontag, Christopher Drew, and Annette Lawrence Drew, Blind Man's Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage (New York: Public Affairs, 2016).

[34] Garrett Hinck, “Cutting the Cord: The Legal Regime Protecting Undersea Cables,” Lawfare (blog), 21 November 2017, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/.

[35] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China (2020).

[36] Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China (2020), 83

[37] Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (Protection of Submarine Cables and Other Measures) Act 2005. https://www.legislation.gov.au/.

[38] “TRAI releases recommendations on ‘Licensing Framework and Regulatory Mechanism for Submarine Cable Landing in India’” (press release, Ministry of Communications [India], 20 June 2023), https://pib.gov.in/.

[39] Elizabeth Roche, “Quad Can Pool Resources to Prevent China from Dominating Global Tech,” Live Mint, 28 June 2021, https://www.livemint.com/. Also see, “Quad Summit” (fact sheet, The White House, 12 March 2021), https://www.whitehouse.gov/.

[41] “Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) & India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC)” (press release, Ministry of External Affairs [India], 9 September 2023), https://www.mea.gov.in/.

[42] "ASEAN Guidelines for Strengthening Resilience and Repair of Submarine Cables," ASEAN, n.d., https://asean.org/.

[43] Government of India, “Invitation for Expression of Interest (EOI): Indigenous Development of High Endurance Autonomous Underwater Vehicle–Anti-Submarine Warfare Project HEAUY-ASW,” Make in India Defence, 24 March 2023, https://www.makeinindiadefence.gov.in/.

The security of subsea cables: an enduring naval challenge - Maritime Foundation

Subsea communications

Naval historian Andrew Boyd examines the strengths and vulnerabilities of subsea communication systems

The history of cable communications goes back to 1837 with Samuel Morse’s invention of the telegraphic cable. The first cross-Channel link was installed in 1851 and the first transatlantic one in 1858; by 1900 there was a vast global network of cables linking all major cities, commercial centres and important military sites.

Once the imperial system was complete, the British planners focused on cable-cutting, to disrupt the communications of potential enemies in wartime. In 1912, the Committee of Imperial Defence approved plans for the Post Office, under Admiralty direction, to cut all Germany’s main international cables, if need be, to isolate it from the outside world. On the outbreak of war in August 1914 HMTS Alert cut German cables from Emden down the Channel to France, Spain, Africa and the Americas. Separate operations severed the cables to Britain, and those between Liberia and Brazil and to the Azores and New York.

Throughout the war the Germans too devoted significant effort and considerable ingenuity to cable-cutting. Initially, they focused on isolating Russia from its Western allies by severing cables in the Black Sea and the Baltic; in response Britain laid new cables to Russia, around northern Norway. From 1915, Germany conducted a sustained attack on cables connecting Britain with neutral countries across the North Sea, but Britain always retained sufficient control of the North Sea to repair damage there, suffering disruption rather than permanent loss. The Germans had initially avoided cutting Allied transatlantic cables, judging that this would harm its own communications as much as those of the Allies, but in the last year of the war, following the American entry, the Germans decided they would now gain more than they lost, and attempted to sever every cable. Most cutting was conducted by U-boats, a technique Germany had mastered over the previous two years. Although many cables were cut, the implementation fell short of the comprehensive and simultaneous impact sought – but the potential of the operation at a critical point of the war was clear.

The effect of HF radio

Unsurprisingly, then, in the early 1920s the Admiralty saw submarine attack on cables as a major potential threat. However, the development of High Frequency (HF), or shortwave, radio revolutionised global communications, transmitting not only traditional telegraphic text but also voice and high-speed teleprinter traffic over intercontinental distances. Between the late 1920s and the 1960s HF radio displaced cable as the preferred means of long-range communication; the first submarine telephone cable was not laid until 1956. Meanwhile, the invention of satellite communication in the mid-1960s suggested that the future would lie there rather than in any extensive return to cable.

In the Second World War the dominance of HF for long-distance, especially transoceanic, communication had meant less cable-cutting; in September 1939, however, the British did cut the German telegraphic cables from Emden to Lisbon, and from Emden to New York via the Azores. The Germans, meanwhile, assessed that British dominance in the Atlantic and Mediterranean and advances in cable repair techniques would render unproductive any attacks on the Allied cables there. In the Pacific and Indian oceans there was more action: the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked British cables and relay stations, sometimes by submarine, and the Royal Navy developed midget submarines for cable attack; at the very end of the war, the midget XE-4 cut the Japanese telegraphic cable linking Saigon to Singapore and Hong Kong. This operation aimed to force the Japanese to resort to radio communication, which was more vulnerable to interception and cryptographic attack.

The Cold War

The perceived vulnerability of radio, and the development of higher capacity cables, drove both sides to move their sensitive communications underground wherever they felt confident of geographic control. Both sides then looked for opportunities to gain covert access to their opponents’ communications by tapping into their cables. This interception resumed what Britain had done to great effect in the First World War, though with one key difference. In the earlier conflict the cable-cutting had forced Germany to use neutral cables which passed across British-controlled territory, and Britain had accordingly been able to demand copies of all traffic, without necessity for taps.

The first big tapping operations of the Cold War, conducted jointly by the British and Americans, attacked Soviet military cables in Vienna and Berlin by tunnelling from Western territory into Soviet-occupied zones. Then in the 1960s the Americans exploited their new submarine technology to attack maritime Soviet targets, and in 1971, they tapped the Soviet cable linking the naval base at Petropavlovsk on Kamchatka to the base at Magadan. This operation, codenamed Ivy Bells, delivered outstanding intelligence for ten years until it was betrayed. By that time the Americans had an even more valuable tap on the Barents Sea cable connecting Severodvinsk with the Soviet Northern Fleet headquarters at Murmansk.

Geography denied the Soviets similar opportunities. But they devoted considerable effort to planning how to attack and disable the American long-range passive sonar chains in the Atlantic and Pacific that were monitoring Soviet submarine movements. It can be assumed that the targeting of undersea cables for intelligence collection or military disruption by states with the relevant capabilities continues to this day.

Fibre-optic

Although over the 30 years from 1956 there were steady improvements in the international telephone network, there were physical limits to the development of traditional copper-based cable. Then in the 1980s came fibre-optic. The first of these cables laid across the Atlantic in 1988 could handle 40,000 simultaneous telephone calls, more than ten times the capacity of the best copper cable. The evolution of this technology was rapid; within a decade fibre-optic cable could handle millions of calls per minute and had supplanted satellite and residual HF radio. Fibre-optic made the internet possible, underpinned its explosive growth, and made cloud computing possible. It has rightly been described as the central nervous system of the global internet, revolutionising international trade and finance, where a typical day may now see ten trillion dollars in financial transfers. By 2022, it was estimated that 99 per cent of global communications used undersea cables, comprising a network of over 400 separate cable systems and 750,000 miles of fibre.

All international activity – business, political, military and personal – now depends on these networks. Furthermore, the integrated nature of the global communications infrastructure and the way traffic is routed means that any single communication probably uses an undersea cable at some point in its journey. National governments accordingly recognise that cables are a vital part of the critical national infrastructure enabling their country to function. However, while networks within a country can be protected by it, undersea cables invariably transit international waters, outside the control of any single jurisdiction, and their status is further complicated because most are owned by private companies. These present, therefore, a major vulnerability.

Threats and remedies

Undersea cables are routed, and strengthened where possible, to minimise the likelihood of accidental damage from fishing or anchoring, or from natural events such as earthquakes or landslides. The networks are designed to be resilient, with built-in redundancy and alternative routes, and rapid response teams to tackle repairs. Even though repairing a broken cable is still challenging and may take several weeks, damage from accidental human intervention or even a large natural event is generally manageable, inflicting inconvenience on users rather than critical loss.

The major threat, with potentially devastating consequences to the functioning of a modern economy and society, comes from attack by a hostile power or a terrorist organisation. Such an attack would target critical chokepoints, including cable landing stations where numerous cables come ashore, and/or simultaneously hit multiple cables offshore for maximum effect and an impact potentially comparable to an attack with weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Conceptually, it would replicate the putative 1918 German attack, but would exploit all the advantages of modern technology to achieve infinitely greater damage.

While a terrorist organisation might be willing to inflict unlimited harm, there would be limits to its resources and expertise, reducing the scope of what it could achieve, especially underwater. Good protection of vulnerable points such as landing stations, network redundancy, regular surveillance of critical cable routes, good intelligence, and an ability to respond rapidly to any perceived threat can reduce such a risk to acceptable levels; in the United Kingdom, threat monitoring and response is coordinated by the Joint Maritime Security Centre, with representation from all relevant agencies.

A state actor may, in contrast, have the resources to inflict huge damage but would have to carefully weigh the benefits and costs of an attack, as did Germany a century ago – but now, in a more globally integrated world, bringing consequences which are harder to predict. The mitigation factors against terrorism all apply to a state threat, but the WMD analogy suggests two other ways of increasing the difficulty and the risk of mounting such an attack: the first is to establish an international legal framework, backed by clear sanctions, to protect undersea cable communications and inhibit actions and capabilities required for an attack; and the second, the final resort, must be deterrence, in that an attacker must be convinced that the probability of a proportionate response is too high.

Dr Andrew Boyd CMG OBE is a former submariner and the author of British Naval Intelligence Through the Twentieth Century (Seaforth), winner of the Maritime Media Awards 2021 Mountbatten Award for Best Book.

China's Digital Aid: The Risks and Rewards

As part of China’s massive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the biggest infrastructure undertaking in the world, Beijing has launched the Digital Silk Road (DSR). Announced in 2015 with a loose mandate, the DSR has become a significant part of Beijing’s overall BRI strategy, under which China provides aid, political support, and other assistance to recipient states. DSR also provides support to Chinese exporters, including many well-known Chinese technology companies, such as Huawei. The DSR assistance goes toward improving recipients’ telecommunications networks, artificial intelligence capabilities, cloud computing, e-commerce and mobile payment systems, surveillance technology, smart cities, and other high-tech areas.

China has already signed agreements on DSR cooperation with, or provided DSR-related investment to, at least sixteen countries [PDF]. But the true number of agreements and investments is likely much larger, because many of these go unreported: memoranda of understanding (MOUs) do not necessarily show whether China and another country have embarked upon close cooperation in the digital sphere. Some estimates suggest that one-third of the countries participating in BRI—138 at this point—are cooperating on DSR projects. In Africa, for instance, China already provides more financing for information and communications technology than all multilateral agencies and leading democracies combined do across the continent.

People take selfies in front of Ethiopian satellite antenna during ceremony for the Ethiopian Remote Sensing Satellite, which was launched by China. Eduardo Soteras/AFP/Getty Images

Leaders of many developing countries, as well as some developed ones such as South Korea, have signed DSR agreements. Although these MOUs are not legally binding, they show the scope of global interest in the DSR. Countries in Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Southeast Asia desperately need inexpensive, high-quality technology to expand wireless phone networks and broadband internet coverage. Overall, the world’s infrastructure financing gap is projected to reach nearly $15 trillion by 2040. DSR-related investments can help fill that gap and spark growth by providing or helping finance this critical infrastructure. Chinese firms are bringing additional benefits to developing countries by establishing training centers and research and development programs to boost cooperation between scientists and engineers in these countries and their Chinese counterparts, and to transfer technical knowledge in areas such as smart cities, artificial intelligence and robotics, and clean energy, among others.

Still, some democracies have raised serious concerns about the Digital Silk Road. They worry that, at a time when Beijing is becoming more assertive on the global stage, China will use the DSR to enable recipient countries to adopt its model of technology-enabled authoritarianism, which would be detrimental to personal freedoms and sovereignty in those countries. Chinese technology companies have already helped governments in other countries develop surveillance capabilities that could be used against opposition groups, and Beijing has provided training for interested DSR recipient countries on how to monitor and censor the internet in real time. Although some of these Chinese companies are nominally private, even the private firms have drawn global scrutiny for state links as they are required by Chinese cybersecurity legislation to store data on servers in China and submit to checks from authorities.

Moreover, allowing Chinese firms to build countries’ fifth-generation (5G) networks and other infrastructure, and to set technology standards that could become the norm in many countries, could risk espionage and coercion of other states’ politics if Beijing used data breaches to blackmail political elites in those states. The DSR could also help recipient countries better control their internets through filtering, content moderation, data localization, and surveillance. Doing so would accelerate a fracturing of the global internet, as some countries pursue these policies of internet control while others remain committed to internet freedoms.

Examples of States Participating in the Digital Silk Road

Click on the interactive map for a sample of countries with which China has signed DSR agreements and where it has launched DSR projects. Case studies of high-profile DSR investments show how China and recipient governments are using DSR and what the potential benefits and harms of their actions are.

Examples of States Participating in the Digital Silk Road

Click on the interactive map for a sample of countries with which China has signed DSR agreements and where it has launched DSR projects. Case studies of high-profile DSR investments show how China and recipient governments are using the DSR and what the potential benefits and harms of their actions are.

- DSR case study

- DSR participating countries

Conclusion

The existing Digital Silk Road deals are just the start. Beijing is making the DSR a bigger foreign policy priority [PDF], as an increasing number of developed countries, including the United States, Australia, Japan, and some European states ban Chinese tech firms from their 5G infrastructure; launch broader strategies to limit Chinese tech giants’ expansion; and try to prevent Beijing from setting standards for the internet, 5G networking, and other areas. Chinese technology firms therefore need even greater growth in developing markets as they are excluded from wealthier states.

The coronavirus pandemic, which has led many governments to monitor their populations, has only added [PDF] to the demand in developing states for Chinese telecommunications and surveillance tools. In response, Beijing has linked the DSR to the Health Silk Road, a subset of the BRI that supports health infrastructure.

But as the DSR expands, concerns about its influence on recipient states will likely mount as well. Some developing countries, such as India, have expressed similar qualms as the United States and Europe have about China’s tech offensive. And policymakers in states such as Myanmar and Malaysia, another country involved in DSR projects, have expressed growing concerns over sovereignty and excessive debt. Beijing’s increasingly brittle and nationalist diplomacy is also undermining its efforts to assuage policymakers in developing states—even longtime close partners like Malaysia—about the potential downsides of DSR and BRI more generally.

Buildings are pictured under construction in Egypt’s New Administrative Capital, in 2020. Chinese banks are financing the new capital. Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters

Chinese construction worker pauses in Lusaka, Zambia, in 2018. China is building and financing most of the digital infrastructure projects in Zambia. Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters

To be sure, China is not the only country whose major tech companies have participated in surveillance, cooperation with their countries’ militaries, and espionage abroad. Some U.S. tech giants have also used their networks to facilitate surveillance, espionage, and defense operations. U.S. companies such as Gatekeeper Systems also have sold facial recognition technology to authoritarian states such as Saudi Arabia. And, regardless of China’s actions, many governments have clear demands for surveillance and artificial intelligence infrastructure, as well as other technologies that raise serious concerns about privacy.

Despite concerns raised by developed states and some developing countries about aspects of DSR, Beijing will keep pushing forward. China has already spent an estimated $79 billion [PDF] on DSR-related projects, and its DSR assistance will likely grow substantially throughout the 2020s. At major China-sponsored international summits such as the World Internet Conference and the Belt and Road Forum, Beijing has promoted [PDF] DSR as a top Chinese priority.

As the Digital Silk Road expands, the conflicts around it—between countries signing up for DSR and those concerned about its downsides and between groups within countries worried about its detrimental effects and some governments that stand to benefit—will only intensify.

Methodology

The interactive map lists states known to be participating in the Digital Silk Road. The list of states was compiled from news reports, studies of DSR and Chinese digital assistance to other countries, and DSR signing agreements. It does not include every country to which China provides some digital aid, financing or investment, as many of these aid and investment deals remain opaque.

Resources

Robert Greene and Paul Triolo, “Will China Control the Global Internet via Its Digital Silk Road?,” SupChina, May 8, 2020.

Paul Triolo, Clarise Brown, Kevin Allison, and Kelsey Broderick, “The Digital Silk Road: Expanding China’s Digital Footprint,” Eurasia Group, April 29, 2020.

“Mapping China’s Tech Giants,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, November 2019.

Clayton Cheney, “China’s Digital Silk Road: Strategic Technological Competition and Exporting Political Illiberalism,” Net Politics (blog), September 26, 2019.

Thomas S. Eder, Rebecca Arcesati, and Jacob Mardell, “Networking the ‘Belt and Road’: The Future Is Digital,” Mercator Institute for China Studies, August 28, 2019.

Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca, “Belt and Road Tracker,” Council on Foreign Relations, last updated May 8, 2019.

“The Digital Side of the Belt and Road Initiative Is Growing,” Economist, February 6, 2020.

Acknowledgments

This interactive was made possible by the generous support of the Ford Foundation.

The author also thanks Elizabeth Economy, senior fellow for China studies; Julian Gewirtz, senior fellow for China studies; Shannon K. O’Neil, vice president, deputy director of studies, and Nelson and David Rockefeller senior fellow for Latin America studies; Adam Segal, Ira A. Lipman chair in emerging technologies and national security and director of the Digital and Cyberspace Policy program; Sheila A. Smith, senior fellow for Japan studies; and research associates Lucy Best and Michael Collins for their comments on drafts of this interactive.

Executive Production

Joshua Kurlantzick, Senior Fellow for Southeast Asia

James West, Research Associate, David Rockefeller Studies Program

Senior Fellow for Southeast Asia

James West

Research Associate, David Rockefeller Studies Program

Editorial Management

Patricia Lee Dorff, Editorial Director

Chloe Moffett, Associate Editor, Publishing

Sumit Poudyal, Associate Editor, Publishing

Katherine De Chant, Associate Editor, Publishing

Editorial Director

Chloe Moffett

Associate Editor, Publishing

Sumit Poudyal

Associate Editor, Publishing

Katherine De Chant

Associate Editor, Publishing

Digital Product Management

Doug Halsey, Chief Digital Officer

Lisa Ortiz, Director of Product and Design

Katherine Vidal, Deputy Director of Design

Donnie Bolen , Web Support Associate

Victoria Brooks, Senior UX | UI Designer

Will Merrow, Data Visualization Designer

Sabine Baumgartner, Photo Editor

Eric Spector, Deputy Director, Digital Development

Karen Mandel, Associate Director of Quality Assurance

Rob Osoria, Lead Developer

Aaron Potter, DevOps Engineer

Gabriel Gonzalez, Developer

Mariano Giagante, Quality Assurance Analyst

Doug Halsey

Chief Digital Officer

Lisa Ortiz

Director of Product and Design

Katherine Vidal

Deputy Director of Design

Donnie Bolen

Web Support Associate

Victoria Brooks

Senior UX | UI Designer

Will Merrow

Data Visualization Designer

Sabine Baumgartner

Photo Editor

Eric Spector

Deputy Director, Digital Development

Karen Mandel

Associate Director of Quality Assurance

Rob Osoria

Lead Developer

Aaron Potter

DevOps Engineer

Gabriel Gonzalez

Developer

Mariano Giagante

Quality Assurance Analyst

Eyes on Asia Newsletter

Get monthly insights and analysis on the latest developments across Asia.

No comments:

Post a Comment