New Fusion Record Achieved in Tungsten-Encased Reactor

Isaac Schultz

Summary

Researchers from Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) used a novel X-ray detector inside the tokamak to measure the plasma's properties, including electron temperature and impurity density. The diagnostic tool, based on a device made by DECTRIS and modified by PPPL researchers, allowed for more accurate measurements compared to existing techniques.

The six-minute plasma duration record, along with a steady-state central electron temperature of 4 keV (50 million degrees Celsius) and an electron density twice that of previous discharges, marks an important step towards developing fusion as a viable energy source. The campaign also explored the "X-Point radiation" plasma scenario, leading to one-minute plasmas with low electron temperature in the divertor, which helps improve the lifespan of plasma-facing components.

New records for power injection systems were achieved, and the tokamak surpassed the milestone of 10,000 plasmas since its first one in December 2016. The WEST tokamak is currently in a shutdown period for maintenance and installation of new systems, with the next experimental campaign set to begin in autumn 2024.

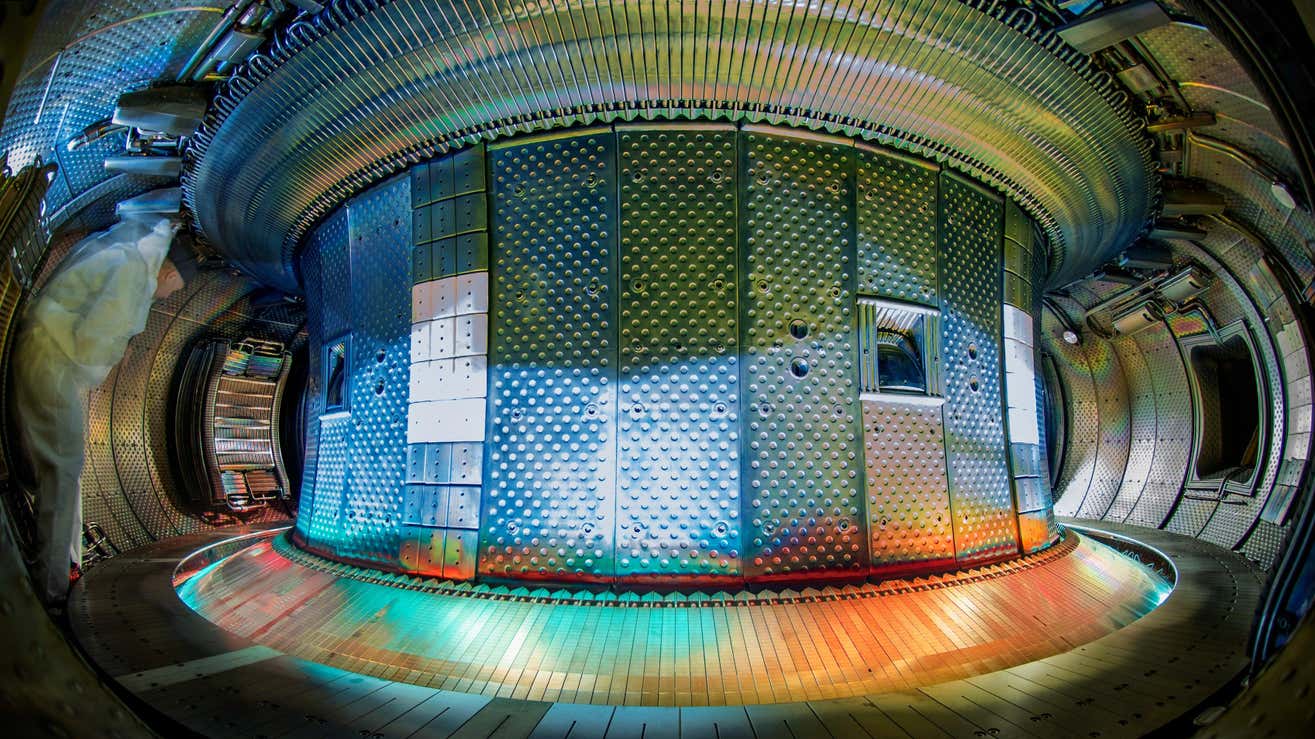

A fusion device ensconced in highly durable tungsten sustained a more energetic, denser plasma than previously recorded.

A

tokamak in France set a new record in fusion plasma by encasing its

reaction in tungsten, a heat-resistant metal that allows physicists to

sustain hot plasmas for longer, and at higher energies and densities

than carbon tokamaks.

A tokamak is a torus- (doughnut-) shaped fusion device that confines plasma using magnetic fields, allowing scientists to fiddle with the superheated material and induce fusion reactions. The recent achievement was made in WEST (tungsten (W) Environment in Steady-state Tokamak), a tokamak operated by the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA).

WEST was injected with 1.15 gigajoules of power and sustained a plasma of about 50 million degrees Celsius for six minutes. It achieved this record after scientists encased the tokamak’s interior in tungsten, a metal with an extraordinarily high melting point. Researchers from Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory used an X-ray detector inside the tokamak to measure aspects of the plasma and the conditions that made it possible.

“These are beautiful results,” said Xavier Litaudon, a scientist with CEA and chair of the Coordination on International Challenges on Long duration OPeration (CICLOP), in a PPPL release. “We have reached a stationary regime despite being in a challenging environment due to this tungsten wall.”

Nuclear fusion occurs when atoms fuse, reducing their total number and releasing a huge amount of energy in the process. It is not to be confused with nuclear fission, the inverse process by which atoms are split to produce energy. Nuclear fission also creates nuclear waste, while nuclear fusion is seen as a potential grail of energy research: a clean process that could be optimized to produce more energy than it took to power the reaction in the first place. Hence the hype around “limitless energy” and similarly optimistic musings.

Earlier this year, the Korea Institute of Fusion Energy installed a tungsten diverter in its KSTAR tokamak, replacing the device’s carbon diverter. Tungsten has a higher melting point than carbon, and according to Korea’s National Research Council of Science and Technology, the new diverter improves the reactor’s heat flux limit two-fold. KSTAR’s new diverter enabled the institute’s team to sustain high-ion temperatures exceeding 100 million degrees Celsius for longer.

“The tungsten-wall environment is far more challenging than using carbon,” said Luis Delgado-Aparicio, lead scientist for PPPL’s physics research and X-ray detector project, and the laboratory’s head of advanced projects, in the same release. “This is, simply, the difference between trying to grab your kitten at home versus trying to pet the wildest lion.”

These are exciting times for fusion (I know, I know, everyone says that). But it’s true! As we reported last year:

Research into nuclear fusion has made slow but significant strides; in 2022, scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory managed net energy gain in a fusion reaction for the first time. We’re still very (read: very) far from the vaunted goal of a reliable, zero-carbon energy source, and the achievement came with caveats, but it nonetheless showed that the field is plodding forward.

We must stress—as we do any time we’re discussing the possibilities of fusion technology—that the road of progress will be meandering, and slow, and in some cases a boondoggle. Every mountain has its molehills; you won’t be able to know their significance in the context of progress unless you keep climbing.

Fusion record set for tungsten tokamak WEST

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy(Link is external)’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) measured a new record for a fusion(Link is external) device internally clad in tungsten, the element that could be the best fit for the commercial-scale machines required to make fusion a viable energy source for the world.

The device sustained a hot fusion plasma(Link is external) of approximately 50 million degrees Celsius for a record six minutes with 1.15 gigajoules of power injected, 15% more energy and twice the density than before. The plasma will need to be both hot and dense to generate reliable power for the grid.

The record was set in a fusion device known as WEST(Link is external), the tungsten (W) Environment in Steady-state Tokamak, which is operated by the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission(Link is external) (CEA). PPPL has long partnered with WEST, which is part of the International Atomic Energy Agency(Link is external)’s group for the Coordination on International Challenges on Long duration OPeration(Link is external) (CICLOP). This milestone represents an important step toward the CICLOP program’s goals. The researchers will submit a paper for publication in the next few weeks.

“We need to deliver a new source of energy, and the source should be continuous and permanent,” said Xavier Litaudon, CEA scientist and CICLOP chair. Litaudon said PPPL’s work at WEST is an excellent example. “These are beautiful results. We have reached a stationary regime despite being in a challenging environment due to this tungsten wall.”

Remi Dumont, head of the Experimentation & Plasma Development Group of the CEA’s Institute for Magnetic Fusion Research(Link is external), was the scientific coordinator for the experiment, calling it “a spectacular result.”

PPPL researchers used a novel approach to measure several properties of the plasma radiation. Their approach involved a specially adapted X-ray detector originally made by DECTRIS(Link is external), an electronics manufacturer, and later embedded into the WEST tokamak(Link is external), a machine that confines plasma — the ultra-hot fourth state of matter — in a donut-shaped vessel using magnetic fields.

Left to right: Xavier Litaudon, CEA scientist and CICLOP chair; Remi Dumont, head of the Experimentation & Plasma Development Group of the CEA’s Institute for Magnetic Fusion Research; and Luis Delgado-Aparicio, PPPL’s head of advanced projects. (Credit: CEA and Michael Livingston / PPPL Communications Department)

“The X-ray group in PPPL’s Advanced Projects Department is developing all of these innovative tools for tokamaks and stellarators around the world,” said Luis Delgado-Aparicio, PPPL’s head of advanced projects and lead scientist for the physics research and the X-ray detector project. This is just one example of PPPL’s strengths in diagnostics: specialized measurement tools used, in this case, to characterize hot fusion plasmas.

“The plasma fusion community was among the first to test the hybrid photon counting technology to monitor plasma dynamics,” said DECTRIS Head of Sales Nicolas Pilet. “Today, WEST achieved unprecedented results, and we would like to congratulate the team on their success. Plasma fusion is a fascinating scientific field that holds great promise for humanity. We are incredibly proud to contribute to this development with our products, and are thrilled by our excellent collaboration."

Scientists worldwide are trying different methods to reliably extract heat from plasma while it undergoes a fusion reaction. But this has proven to be particularly challenging, partly because the plasma must be confined long enough to make the process economical at temperatures much hotter than the center of the sun.

PPPL’s Tullio Barbui, Novimir Pablant and Luis Delgado-Aparicio work on their multi-energy soft X-ray detector (ME-SXR) at DECTRIS, the company that made the device that formed the basis for their detection system. (Photo credit: DECTRIS)

A previous version of the device — Tore Supra — achieved a slightly longer reaction, or shot, but back then, the machine’s interior was made of graphite tiles. While carbon makes the environment easier for long shots, it may not be suitable for a large-scale reactor because the carbon tends to retain the fuel in the wall, which will be unacceptable in a reactor where efficient recovery of tritium from the reactor chamber and reintroduction into the plasma will be paramount. Tungsten is advantageous for retaining far less fuel, but if even minute amounts of tungsten get into the plasma, radiation from the tungsten can rapidly cool the plasma.

“The tungsten-wall

environment is far more challenging than using carbon,” said

Delgado-Aparicio. “This is, simply, the difference between trying to

grab your kitten at home versus trying to pet the wildest lion.”

Novel diagnostic measures record shot

The shot was measured using a novel approach developed by PPPL researchers. The hardware for the measurement tool, or diagnostic, was made by DECTRIS and modified by Delgado-Aparicio and others on his research team, including PPPL researchers Tullio Barbui, Oulfa Chellai and Novimir Pablant. “The diagnostic basically measures the X-ray radiation produced by the plasma,” Barbui said of the device, known as a multi-energy soft X-ray camera (ME-SXR). “Through the measure of this radiation, we can infer very important properties of the plasma, such as the electron temperature in the real core of the plasma, where it is the hottest.”

Off the shelf, the DECTRIS diagnostic can normally be configured with all pixels set to the same energy level. PPPL developed a novel calibration technique that allows them to set the energy independently for each pixel.

Barbui said the approach has advantages over the existing technique used in WEST, which can be hard to calibrate and generates readings that are sometimes affected by the radio frequency waves used to heat the plasma. “Radio frequency waves don’t bother our diagnostic,” Barbui said.

“During the six-minute shot,

we were able to measure quite nicely the central electron temperature.

It was in a very steady state of around 4 kilovolts. It was a pretty

remarkable result,” he said.

Searching for light at the right energy levels

The diagnostic looks for light from a specific kind of radiation known as Bremsstrahlung, which is produced when an electron changes direction and slows down. The initial challenge was figuring out what frequencies of light from Bremsstrahlung to look for because both the plasma and the tungsten walls can emit this sort of radiation, but the measurements need to focus on the plasma. “The photon energy band between 11 and 18 kiloelectronvolts (keV) offered us a nice window of opportunity from the core emission never explored before and thus influenced our decision to carefully sample this range,” said Delgado-Aparicio.

“Normally, when this technique is applied, you make only two measurements. This is the first time we have taken a series of measurements,” Barbui said.

In the image above, the red line represents the plasma’s edge. The yellow lines represent the many lines of sight of the ME-SXR diagnostic so that it can thoroughly evaluate the plasma. The diagnostic readings can be used to calculate the temperature of the electrons in the plasma, the plasma charge and the density of impurities in the plasma. (Image credit: Luis Delgado-Aparicio and Tullio Barbui / PPPL)

Delgado-Aparicio also pointed out that “the special calibration of our detector allowed us to obtain readings for each energy level between 11 and 18 keV, for each line of sight from the camera, while sampling the entire cross section.” Approximately 10 measurements are taken per second. The trick is to use the intensity from the lowest 11 keV energy as a reference level, and measurements from the other seven intensities are compared to the initial one. Ultimately, this process produces seven simultaneous temperature readings per line of sight, hence the high accuracy of the measurement. “This innovative capability is now ready to be exported to many machines in the U.S. and around the world,” said Delgado-Aparicio.

“From the eight different intensity measurements, we got the best fit, which was between 4 and 4.5 kilovolts for the core plasma. This represents nearly 50 million degrees and for up to six minutes,” said Delgado-Aparicio.

The diagnostic readings can be used not only to calculate the temperature of the electrons in the plasma but also the plasma charge and the density of impurities in the plasma, which is largely tungsten that has migrated from the tokamak’s walls.

Each curve represents a different intensity from each energy-level reading. Note that the vertical y-axis represents the number of counts, with the highest number being close to 6×105 or 600,000 photons of X-ray light. (Image credit: Luis Delgado-Aparicio and Tullio Barbui / PPPL)

“This particular system is the first of this kind with energy discrimination. As such, it can provide information on temperature and many details on the precise impurity content — mainly tungsten — in the discharge, which is a crucial quantity to operate in any metallic environment. It is spectacular,” said Dumont. While this data can be inferred from several other diagnostics and supported with modeling, Dumont described this new method as “more direct.”

Barbui said the diagnostic can gather even more information in future experiments. “This detector has the unique capability in that it can be configured to measure the same plasma with as many energies as you want,” Barbui said. “Now, we have selected eight energies, but we could have selected 10 or 15.”

Litaudon said he is pleased to have such a diagnostic on hand for the CICLOP program. “In fact, this energy-resolving camera will open a new route in terms of analysis,” he said. “It’s extremely challenging to operate a facility with a tungsten wall. But thanks to these new measurements, we will have the ability to measure the tungsten inside the plasma and to understand the transport of tungsten from the wall to the core of the plasma.”

Litaudon says this could help them minimize the amount of tungsten in the plasma’s core to ensure optimal operating conditions for fusion. “Thanks to these diagnostics, we can understand this problem and go to the root of the physics for both measurement and simulation.”

Time-intensive computer calculations carried out by CEA’s Dumont, Pierre Manas and Theo Fonghetti also confirmed good agreement between relevant simulations and the measurements reported by the PPPL team.

Dumont also noted that the ME-SXR camera builds on the Lab’s important diagnostic work at WEST. “The ME-SXR is only part of a more global contribution of diagnostics from PPPL to CEA/WEST,” Dumont said, noting the hard X-ray camera and the X-ray imaging crystal spectrometer. “This collaboration helps us a lot. With this combination of diagnostics, we will be able to perform very accurate measurements in the plasma and control it in real-time.”

This novel technology

development and research program was funded by a DOE early career award

and a diagnostic development grant that Delgado-Aparicio won in 2015 and

2018, respectively, under grant DE-AC02-09CH11466.

About the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA)

The CEA informs public decision-making and provides concrete scientific and technological solutions to dynamic forces (businesses and communities) in major societal domains: energy and digital transitions, future health, defense, and global security. The CEA conducts fundamental research activities in biotechnology and health, materials science and the Universe, physics, and nanoscience. The Institute for Magnetic Fusion Research (IRFM) is a key player in the field of magnetic fusion research in Europe, operating under the CEA at the Cadarache Centre. With over 200 experts, IRFM is deeply involved in supporting the ITER project, the JT-60SA operation, and advancing magnetic confinement fusion research within the EUROfusion consortium. Its strategy encompasses a broad spectrum of activities aimed at preparing for the operation of next-generation fusion devices and contributing to the global fusion research community's efforts towards developing a fusion power plant.

CEA Media Contact: presse@cea.fr, 33 1 64 50 20 11

About DECTRIS

DECTRIS Ltd. develops and manufactures state-of-the-art X-ray and electron detection cameras to spark scientific breakthroughs around the world. While photographic cameras capture visible light, DECTRIS cameras count individual X-ray photons and electrons. DECTRIS is the global market leader at synchrotron light sources. Laboratories also achieve high-quality results with our technology. Our detectors played for example a decisive role in the determination of the structures of the coronavirus. Our impact extends to research in the sectors of energy, the environment, and industry, and we offer novel solutions for medical applications. We support researchers everywhere from our offices in Switzerland, Japan and the United States. More at www.dectris.com(Link is external).

DECTRIS media contact: Clara Demin, clara.demin@dectris.com, +41 (0) 56 500 31 51

About Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL)

Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory is a U.S. Department of Energy national laboratory managed by Princeton University.

PPPL media contact: Rachel Kremen, rkremen@pppl.gov, +1 (609) 552-1135

IRFM West - New Plasma Duration Record Set by WEST Tokamak

May 07, 2024

New Plasma Duration Record Set by WEST Tokamak

Equipped with superconducting coils and tungsten plasma-facing actively cooled components, the WEST tokamak has achieved a new plasma duration record of over 6 minutes, with a steady-state temperature of 50 million degrees Celsius (4 keV).

The latest experimental campaign of WEST commenced in mid-January 2024 and concluded on April 26 after a four-month experimentation period.

During this campaign, a new plasma duration record of 6 minutes and 4 seconds was achieved, with an injected energy of 1.15 GJ, a steady-state central electron temperature of 4 keV (50 million degrees Celsius), and with an electron density twice that of discharges obtained in the tokamak's previous configuration, Tore Supra. The electron temperature was measured, notably through a new method developed by collaborators from the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL). This new diagnostic can be used not only to measure electron temperature in the plasma but also the density of impurities, largely composed of tungsten eroded from the wall and migrated into the plasma core. Measuring and controlling the quantity of impurities are crucial for the operation of a tokamak in a metallic environment, as these impurities can cause rapid cooling of the plasma or even contribute to its sudden extinction.

In addition to the plasma duration record, the latest experimental campaign made progress in other areas. The "X-Point radiation" plasma scenario was explored, leading to the achievement of one-minute plasmas with low electron temperature (Te < 5 eV) in the divertor. These radiating plasmas allow for a better distribution of heat fluxes on the plasma-facing components, significantly improving their lifespan. Several new diagnostics, some developed and installed by international collaborators, were successfully deployed, providing new measurements to characterize core and edge plasma. New records for power injection systems were also achieved, with 5.8 MW injected by the lower hybrid heating and current drive system and over 4 MW by the ion cyclotron resonance heating system. The latter system was also used to study a method for conditioning the tokamak walls, a method envisaged for ITER tokamak wall conditioning.

Finally, during this campaign, WEST surpassed the milestone of 10,000 plasmas since the first one was achieved in December 2016.

The tokamak is now in a shutdown period for maintenance and to install new systems. The next experimental campaign will commence in the autumn of this year.

Last update : 05/07 2024 (944)

No comments:

Post a Comment