AI Model Makes Ionospheric Predictions from Space Weather

MARCH 22, 2025 - Egyptian and Chinese Scientists at Wuhan University, Wuhan, Hubei, China have developed a groundbreaking artificial intelligence system that promises to dramatically improve predictions of ionospheric electron density from space weather conditions, potentially safeguarding satellite communications and navigation systems worldwide.

In a study published in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, researchers introduced the Attention-Based Recurrent ResNet18 (ABRR-18) model, a sophisticated deep learning system for predicting ionospheric electron density.

"This represents an advancement in our ability to model the ionosphere, especially during severe geomagnetic storms," said Dr. A. Abdelaziz, lead author of the study. "However, the improvements over existing models vary significantly depending on altitude."

The ionosphere—a layer of charged particles in Earth's upper atmosphere—directly affects radio signal transmission and GPS accuracy. During severe space weather events, unpredictable changes in the ionosphere can disrupt critical communications and navigation systems.

The new ABRR-18 model utilizes 21 years of data from multiple satellite missions, including CHAMP, COSMIC-1, FY-3C, and COSMIC-2, to predict electron density in the ionosphere's F-layer. The model analyzes "refraction effects that occur as the signals traverse the ionosphere" to determine vertical electron density distributions with high resolution.

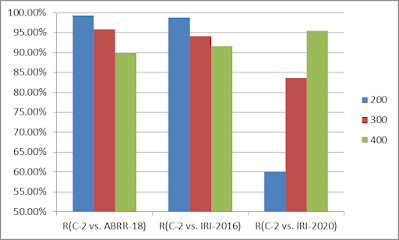

Comparative testing revealed mixed results across different altitudes. At lower altitudes (200 km), ABRR-18 achieved a 99.29% correlation with COSMIC-2 observations, only marginally better than the established IRI-2016 model at 98.88%. At middle altitudes (300 km), ABRR-18 showed a modest improvement with 95.87% correlation versus 94.09% for IRI-2016. However, at higher altitudes (400 km), ABRR-18 underperformed with 90% correlation compared to IRI-2016 (91.57%) and IRI-2020 (95.43%).

"The results highlight the continuing challenges in ionospheric modeling," explained Dr. Maria Chen, an ionospheric physicist not involved in the study. "While ABRR-18 shows modest improvements at lower altitudes, the established IRI models still perform better at higher altitudes where many satellites operate."

The development comes as the scientific community has increasingly turned to deep learning for ionospheric modeling. Previous models have faced limitations in validation approaches due to "the magnitude of the problem" in accurately representing ionospheric behavior.

The model showed its best performance during severe geomagnetic storms—achieving a correlation of 0.972 during disturbed conditions, compared to 0.965 during quiet periods—a promising characteristic for space weather forecasting.

"This research represents an incremental step forward rather than a revolutionary breakthrough," said communications engineer Dr. James Foster. "Different models excel at different altitude ranges, suggesting that an ensemble approach combining multiple models might be the most effective strategy moving forward."

A significant limitation of the study is that the model was only evaluated for latitudes between 40°S and 40°N—the range covered by the COSMIC-2 mission data. No performance testing was conducted at high latitudes (above 45 degrees), where ionospheric behavior differs considerably due to proximity to polar regions and greater influence from solar wind and geomagnetic activity. This leaves a substantial gap in understanding how the model might perform in these regions, which are critical for global navigation and communication systems.

The researchers plan to collaborate with space agencies to implement an operational forecasting system that leverages the strengths of ABRR-18 at lower altitudes while incorporating IRI models for higher altitude predictions.

End of release

Global Ionospheric F-Layer Electron Density Prediction Based on Multiple Radio Occultation Data Using Attention-Based Deep Learning Model

A. Abdelaziz et al., "Global Ionospheric F-Layer Electron Density Prediction Based on Multiple Radio Occultation Data Using Attention-Based Deep Learning Model," in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 63, pp. 1-16, 2025, Art no. 4103616, doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2025.3546248.

Abstract: Understanding low-latitude F-layer ionospheric electron density (Ne) under severe geomagnetic conditions is crucial for various GNSS applications. Existing ionospheric models utilizing machine learning (ML) have struggled to accurately capture the complex dynamics of Ne, particularly under extreme geomagnetic conditions. In this study, we propose the attention-based recurrent ResNet18 (ABRR-18) model to predict ionospheric Ne using radio occultation (RO) data obtained from multiple satellite missions between 2002 and 2023. The proposed model integrates ResNet18 and bidirectional-long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM) with a spatial attention mechanism (SAM). Besides, it incorporates various space weather indicators such as solar flux, sunspot number, disturbance storm time, and interplanetary magnetic field (IMF). Experimental results revealed that ABRR-18 outperformed other applied models, such as artificial neural network (ANN)-international reference ionosphere (IRI), ANN-TDD, least-squares boosting (LSBoost), Bi-LSTM, and AlexNet-Bi-LSTM-SAM, achieving a correlation of 0.9674 and a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of $1.0295 \times 10^{5}$ ele/cm3. ABRR-18 showed superior performance under severe geomagnetic conditions and during high solar activity years over the IRI-2016 model. In addition, the ABRR-18 model outperforms the IRI-2016 and IRI-2020 models, with predictions closely aligning with incoherent scatter radar (ISR) observations, particularly during extreme conditions. Compared to the IRI model (IRI-2016 and IRI-2020), ABRR-18 demonstrated superior accuracy in characterizing global ionospheric spatial–temporal properties. This study underscores the potential of deep learning (DL) techniques in ionospheric modeling by exhibiting superior performance. The ABRR-18 model introduces an innovative approach, offering notable advancements in comprehending and predicting ionospheric Ne in challenging conditions.

keywords: {Predictive models;Data models;Training;Solid modeling;Ionosphere;Feature extraction;Data mining;Artificial intelligence;Accuracy;Geomagnetic storms;Electron density;F-layer;ionosphere modeling;radio occultation (RO);recurrent ResNet18;spatial attention mechanism (SAM)},

URL: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=10908888&isnumber=10807682

Introduction

Predicting ionospheric electron density (Ne) during severe geomagnetic conditions and high solar activity periods is critical for various applications, including space weather forecasting, satellite communications, navigation systems (e.g., GPS), and ionospheric research. The ionosphere experiences regular and irregular variations throughout the day and night, influenced by factors such as daily and seasonal variations, sporadic E, ionospheric storms, the 11-year sunspot cycle, and both Earth-based and anthropogenic events. As a result, modeling Ne presents significant challenges.

For decades, scientists have employed various methods to study ionospheric Ne. Early investigations primarily used ground-based ionosondes, which detect the time delay of radio signals reflected from the ionosphere, to measure Ne [1]. Researchers subsequently developed empirical models based on statistical analysis of past ionosonde readings, such as the International Reference Ionosphere (IRI) and the Ne-Quick models [2], [3].

With advancements in computing capabilities, numerical models gained prominence [4]. These models use physics-based equations to describe plasma behavior in the ionosphere [5]. Various ionospheric models, including IRI, Ne-Quick, the thermosphere-ionosphere electrodynamics general circulation model, the global self-consistent model of the thermosphere, ionosphere, and protonosphere, and the ground-to-topside model of the atmosphere and ionosphere for aeronomy, have been developed to provide global predictions of Ne based on inputs such as solar activity indices and geographic location.

Despite the significance of IRI [2], [6] for understanding ionospheric disturbances, recent studies indicate that its predictions frequently differ significantly from observational data [7], [8]. To address this issue, a new method is proposed to improve the IRI-2016 vertical Ne profile by incorporating in situ Ne values from the Swarm A, B, and C satellites [9]. However, ionospheric observation technologies, such as ground- and GPS-based instruments, struggle to consistently measure Ne across all global regions [10]. This inconsistency is particularly pronounced in low-latitude and polar regions, where the scarcity of observations complicates accurate ionospheric imaging, particularly regarding the altitude distribution of Ne. Traditional ground-based Digisondes primarily measure zenithal ionospheric data, limiting their ability to profile bottom-side electron densities.

In recent years, artificial neural networks (ANNs) have gained traction in ionospheric modeling due to their ability to map complex relationships between input vectors and output results. Over the past two decades, studies have successfully used ANNs to solve complex nonlinear problems, including predicting ionospheric parameters such as global total electron content (TEC) [11], [12], [13], the critical frequency of the F2 layer (foF2), and peak Ne (NmF2) [14], [15], [16]. For example, Tang et al. [16] introduced a model that combines a local attention mechanism with a long short-term memory (LSTM) network (LAM-LSTM) for short-term ionospheric TEC forecasting. This model outperformed traditional deep learning (DL) and machine learning (ML) methods, achieving a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 1.35 TECU, compared to 1.54 TECU for the LSTM model and 1.74 TECU for the backpropagation mode.

In addition, Ren et al. [17] proposed a new DL-based multimodel ensemble method (DLMEM) for forecasting ionospheric TEC during geomagnetic storm events, demonstrating a 43.6% reduction in RMSE compared to their previous model [18], especially during the recovery period of geomagnetic storms. Shi et al. [15] introduced an advanced foF2 forecasting model that integrates sample entropy (SE)-optimized DL with LSTM, leveraging the ICEEMDAN approach. Their model exhibited accurate foF2 estimation during both geomagnetically calm and storm periods based on statistical analysis.

Despite these advancements, accurately modeling ionospheric Ne behavior during both quiet and severe events remains a challenge. The GNSS radio occultation (RO) technique offers valuable capabilities for profiling the global, 3-D structure of the ionosphere. However, most previously developed models have relied on derived space-based data as well as simulated, empirical, or ground-based data, often performing poorly during disturbed and high solar activity periods than during quiet periods [19], [20].

For instance, Li et al. [19] introduced the feedforward neural network model [ANN-three-dimensional density model (TDD)], which utilized data from two satellite missions and one ground-based mission over a 12-year period. While ANN-TDD performed well on quiet days during low and high solar activity, it struggled during severe geomagnetic storms, particularly at Millstone Hill Station, where it was less effective than the IRI-2016 in capturing the dynamic evolution of the ionosphere. Similarly, Yang and Fang [20] developed ANN-IRI, a low-latitude, 3-D ionospheric Ne model based on 14 years of Constellation Observing System for Meteorology, Ionosphere, and Climate-1 (COSMIC-1 or C-1) RO profiles and corresponding IRI-2016 Ne data. Although ANN-IRI showed good consistency in the altitude range above 50 km, it relied on IRI values and spline interpolation for lower altitudes, resulting in decreased performance during active periods.

A thorough review of the literature reveals that while ML techniques have been widely used to predict ionospheric Ne, advanced DL techniques have received relatively less attention. Traditional approaches often face inherent limitations such as insufficient accuracy, an inability to capture complex temporal and spatial dependencies, and reliance on handcrafted features that may not fully represent the underlying data patterns. In this study, we employ an advanced DL approach for modeling the ionospheric Ne profile. Our model integrates a deep residual network (ResNet) for feature extraction, bidirectional-LSTM (Bi-LSTM) for feature summarization, and an attention mechanism to focus on the most relevant information. This innovative approach aims to overcome the shortcomings of existing ML methods by manipulating the capabilities of DL and attention modules to improve prediction accuracy and robustness, thereby advancing ionospheric research, especially under severe conditions.

Unlike previous studies [19], [20], our model specifically targets latitudes covered by the COSMIC-2 or C-2 mission, which spans from 40°S to 40°N. It targets low altitudes, primarily the F-layer region (150–500 km), using data from mid-Solar Cycle 23 to mid-Solar Cycle 25. In addition, we incorporate data from the CHAMP, COSMIC-1, and Feng-Yun-3C (FY-3C) missions, covering a period of 21 years. Based on this, we developed a 3-D Attention-Based Recurrent ResNet18 model, known as ABRR-18, for predicting ionospheric Ne.

Our evaluation strategy provides a comprehensive assessment of ABRR-18 performance against other applied ML and DL models in our study. We divide the test data based on geomagnetic storm conditions and periods of high and low solar activity to ensure robustness across various challenging scenarios. The performance of the proposed model is then gauged using ground-based RO data—incoherent scatter radar (ISR)—during various solar activity periods and recent severe geomagnetic storms in 2017 and 2023, as well as against the IRI-2016 and 2020 models.

In our analysis, we also consider key input parameters utilized in the IRI models, which include solar indices (such as the F107 daily index, 81-day, and 12-month running means), sunspot numbers (12-month running mean), the ionospheric index (ionosonde-based IG index and 12-month running mean), and magnetic indices (3-h ap and daily ap). Finally, we assess the ability of our model to capture global ionospheric spatial–temporal characteristics by comparing results with independent datasets from C-2, IRI-2016, and IRI-2020 for the March equinox in 2024.

Marew et al. [21] compared vertical TEC estimates from IRI-2020 and IRI-2016 with GPS-TEC measurements. The results showed that while IRI-2020 showed improvements in modeling positive TEC enhancements during geomagnetically active periods, IRI-2016 outperformed it in several key areas, specifically in handling negative storm conditions. This suggests that IRI-2016 may be more reliable for capturing specific ionospheric behaviors under challenging conditions. In addition, Sherif et al. [22] displayed that IRI-2020 outperforms IRI-2016 during minor geomagnetic storm events. Due to the ambiguity of the results of these studies, we chose IRI-2016 and IRI-2020 to validate our model across various space weather scenarios.

This article outline is as follows. Section II provides an overview of the data and selected variables. Section III delves into the architecture of the proposed ABRR-18 model, detailing its design and implementation. This section outlines the step-by-step process for using the ABRR-18 model to develop a novel Ne profile model, leveraging the proposed variables. Section IV offers a comprehensive overview of the extensive experimental work conducted on the developed model, detailing various tests to rigorously assess its performance. The evaluation involves a thorough comparison with existing models. The conclusion is presented in Section V.

Datasets

Following the success of the COSMIC-1 (C-1) mission, the United States and Taiwan launched the COSMIC-2 (C-2) mission. The C-2 satellites collect data on Earth’s atmosphere by measuring the bending of GPS signals just before they are obstructed by the Earth’s horizon [23], [24]. Due to C-2’s demonstrated consistency in analyzing data alongside Spire Global CubeSats, Digisonde, and ISR data during storm events [25], it is highly recommended for producing accurate Ne estimations. This is the pioneering study that uses four years of C-2 data to model the Ne profiles based on the ResNet18 technique.

We used the RO data spanning 21 years, from March 25, 2002, to December 31, 2023, covering nearly two complete solar cycles, to capture the changing patterns in Ne behavior. Data from CHAMP (2002–2006), C-1 (2007–2015), and C-2 (2020–2023) were obtained from the UCAR community programs (https://data.cosmic.ucar.edu/), while FY-3C mission data (2016–2019) were sourced from the Chinese platform at http://data.nsmc.org.cn.

Space-borne measurements may be affected by equipment failure or extreme solar-terrestrial events, making it important to examine RO profiles for quality control. The following checks were conducted to prevent noisy and erratic profiles: First, profiles with negative values at altitudes of 100 km or higher are omitted. In addition, hmF2 values outside the range of 200–450 km are eliminated [20]. After data quality verification, we select Ne sites at heights within the F-layer, ranging from 150 to 500 km, with profiles recorded every 15 min to develop our model. The quantity of RO-retrieved Ne profiles from all missions every three months from 2002 to 2023 is depicted in Fig. 1(a). The yellow bar represents profiles after data quality control, while the blue bar shows the total number of profiles. The C-1 and C-2 missions surpass the CHAMP and FY-3 C missions in profile numbers, as shown in Table I.

Number of profiles before and after quality control on the data from March 2002 to December 2023 in blue and orange color in (a)–(f) represent the profiles distribution, solar, and geomagnetic indices used in our model represented in F10.7, Dst, Bz, and R indices.

The solar-terrestrial environment, geomagnetic storms, and interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) significantly affect ionospheric Ne, which in turn affects positioning and navigation accuracy. Solar activity is measured using the sunspot number (R) and the solar flux (F10.7) index in nanotesla, representing the level of solar radiation at a wavelength of 10.7 cm in Earth’s orbit. Geomagnetic storms are assessed by the disturbance storm time (Dst) index, also measured in nT. Furthermore, the up component of the IMF (Bz), measured in nT, serves as a space weather index to represent the physical behavior of Ne in the F-layer, as shown in Fig. 1(b)–(e) from 2002 to 2023.

Fig. 1(d)

illustrates the variation of these indices across both low and high

solar activity periods, including quiet and storm times, with the red

horizontal line indicating Dst

Moreover, Fig. 2

displays histograms of all parameters, offering concise summaries of

their frequency distributions and insights into the factors controlling

Ne variations. The histograms reveal that latitude and longitude have

relatively even frequency distributions (skewness = 0.03209 and

0.02506). Conversely, the frequency distributions for time, year, DOY,

and Dst display negative skewness (skewness

Histograms of all parameters in dataset with frequency distribution for each parameter.

The use of histograms and skewness analysis is significant for several reasons. Histograms provide a visual summary of the frequency distribution of each parameter, allowing for a quick assessment of data spread. Skewness measures the asymmetry of these distributions, helping to identify patterns, trends, and anomalies. Negative skewness indicates higher frequencies of higher values, as seen in time, year, DOY, and Dst, while positive skewness suggests a clustering around lower values with occasional high peaks, as observed in altitude, Bz, R, F10.7, and Ne. Understanding these distribution patterns is crucial for identifying how different parameters influence Ne. For instance, the even distribution of latitude and longitude suggests no geographic bias in Ne variations. Positive skewness in parameters such as alt, Bz, R, F10.7, and Ne indicates that these factors may cluster around lower values with some extremely high values, pointing to specific space weather events affecting Ne.

These insights are vital for improving predictive models, including our proposed model. Recognizing the nature of data distribution aids in selecting appropriate statistical methods and algorithms, thereby enhancing model accuracy. This, in turn, supports practical applications such as satellite communication and navigation systems, where accurate predictions of Ne are essential for mitigating potential disruptions.

Methodology

As previously stated, ML methods, particularly ANNs, have been utilized for estimating Ne profiles, as demonstrated in [19] and [20]. In our evaluation, we applied their models, known as ANN-TDD and ANN-IRI, to our data strategy, assessing their performance using only satellite mission data. This evaluation period from the typical 12 or 14 years to an extensive 21-year span.

Given the suboptimal performance of these models, we introduced least-squares boosting (LSBoost), a robust ML method for regression tasks. LSBoost belongs to the family of boosting algorithms, which build predictive models by sequentially combining predictions from multiple base estimators, typically decision trees. It is particularly suited for regression problems as it minimizes the least-squares loss function during training [26].

Although LSBoost still performed poorly, it did slightly outperform the ANN-TDD and ANN-IRI models. This underscores the need for more advanced techniques to accurately model ionospheric Ne profiles based solely on RO data.

Convolutional layers in convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have proven effective in uncovering hidden nonlinear features from raw data [27]. However, relying solely on CNN is neither potent nor convenient due to the complexity of input sample morphology and the potential presence of irrelevant or redundant parts in the collected data. Therefore, the presented model is a DL architecture that integrates seasoned CNN with Bi-LSTM on top of spatial attention mechanism (SAM).

ResNet18 is designed for feature extraction from the input data, while Bi-LSTM layers are used to summarize the local feature series. Finally, SAM enables the model to concentrate on pertinent spatial regions. Accordingly, the proposed model comprises three main parts: Resnet18, Bi-LSTM, and SAM, called ABRR-18. The proposed model merges these parts to create an efficient system for Ne prediction. The system processes input sample parameters through the ResNet18 model to extract an optimal combination of deep features. The recurrent layers then transform these deep feature maps into global vectors ready for regression. SAM enables the model to effectively capture both local and global dependencies within the input samples.

In addition, our dataset was gathered from different satellite missions as previously stated, resulting in diverse values across different spatial areas. SAM can adjust to this diversity, enhancing the model capacity to generalize across various contexts. SAM empowers the model to prioritize the most informative relationships, potentially leading to more precise estimations. Finally, a regression layer is employed to produce the final prediction values. The forecast resolution of the proposed method is one day, utilizing data that can be collected every 15 min throughout the day. Fig. 3 presents the detailed architecture of the proposed model. Table II outlines each layer in the proposed model.

Furthermore, to meticulously evaluate the proposed model, a series of comparative analyses were conducted to validate the crucial role of each component. Specifically, we compared ABRR-18 with one of its core components, Bi-LSTM, to determine whether a simpler model, such as Bi-LSTM alone, could suffice for the task. Given the renowned effectiveness of LSTMs in sequential modeling processing and capturing characteristics of massive data, Bi-LSTM is often considered suitable for predicting future values based on historical data, as it retains information over long sequences [17], [28]. By gauging the performance of the Bi-LSTM on the raw data, we aimed to determine if the additional complexity introduced by ResNet18 and the attention mechanism offers a tangible benefit. In addition, we highlighted the significance of using Bi-LSTM to capture both past and future dependencies in the data.

Moreover, the strategic choice of ResNet18 was justified by developing a variant of ABRR-18, in which ResNet18 was replaced with AlexNet. This alternative model retained the Bi-LSTM and attention mechanism, allowing us to isolate the impact of the feature extraction network. ResNet18 and AlexNet are both well-regarded CNN, but they have different architectures and strengths. By comparing the performance of our original model to the AlexNet variant, the superior feature extraction capabilities of ResNet18 are demonstrated. ResNet18 has the potential to maintain the complex features necessary for accurate prediction. Through these rigorous evaluations, we established the contributions of each component to the overall performance of our proposed model, validating the design choices and highlighting the significance of each component. The remainder of this section details the three parts that manufacture the ABRR-18.

A. Resnet18

Resnet18 is a type of CNN that is part of the ResNet family, introduced by Hattiya et al. [29]. The main innovation of ResNet18 and its variants is the introduction of residual connections, which help mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, allowing the training of much deeper networks. Resnet18 is a deep neural network originally designed for image classification tasks. It consists of 18 layers, including convolutional layers, batch normalization layers, ReLU activation functions, and fully connected layers. The hallmark of ResNet architectures is the use of residual connections, which allow the network to learn identity mappings and facilitate the training of deeper networks. Herein, a 1-D version of Resnet18 has been developed. This network was chosen for its popularity and distinct architecture. Moreover, the convolutional filters in these architectures extract information from regions rather than individual values, making them successful in classifying sequential data. Adaptation is achieved by flattening the convolutional filters and pooling layers into 1-D.

The defining feature of ResNet18 is the residual connection, which can be expressed as

B. Bi-LSTM

In this phase, the feature maps undergo transformation into global vectors. Two recurrent layers, with 100 and 20 neurons, are utilized to define the characteristics of these global vectors. The number of neurons in each layer determines the length of the vector. Consequently, these layers determine which features to retain from the Resnet18 at each time step before forwarding them to the SAM layer. Bi-LSTM was experimented with as the recurrent layer.

C. Spatial Attention Mechanism

The self-attention mechanism is a powerful component in neural networks that has significantly advanced the field of computer vision. It allows a model to weigh the importance of different elements in an input sequence dynamically, enabling it to capture dependencies regardless of their distance from each other [30]. This contrasts with traditional CNNs that primarily focus on local context or sequential dependencies. SAM revolutionizes how neural networks process sequential data by enabling efficient and flexible handling of dependencies within the input.

Therefore, following the Bi-LSTM layers, the model engages SAM. The feature maps derived after the last recurrent layer undergo processing via SAM. Instead of computing a single set of attention scores, multihead SAM is exploited to enable the model to concentrate on pertinent spatial regions. Multihead SAM partitions the input data into several heads, each representing a distinct subspace within the feature space. For every head, the input is projected into three separate spaces: key (K), query (Q), and value (V). Subsequently, attention scores (A) are computed utilizing a scaled dot-product attention mechanism, outlined as follows:

Subsequently, the scaled attention scores (A) are utilized to calculate the ultimate attention output, denoted as

D. ABRR-18 Implementation and Evaluation

In our study, the entire dataset of RO-retrieved Ne profiles, spanning a 21-year period, was shuffled and divided into two sets: 80% for training and 20% for testing to ensure adequate data dispersion. Prior to shuffling and splitting, we selected four representative days from each year—corresponding to the equinoxes and solstices—and added them to the test set to capture seasonal variability.

During the training process, the RMSE was chosen as the loss function due to its effectiveness in evaluating regression models. The Adam optimizer was utilized for its adaptive learning rate capabilities, which help in converging faster and avoiding local minima. The learning rate was set to 0.001, and the model was trained for 40 epochs using a MiniBatchSize of 8192 to efficiently process large datasets. Consistent hyperparameters were maintained for both AlexNet and ResNet18 models to ensure a fair comparison between architectures.

Hyperparameters were tuned using a grid search approach, testing different combinations of learning rates, batch sizes, and dropout rates to identify the optimal configuration. This method ensured that the model parameters were fine-tuned to achieve the best performance. Performance was primarily evaluated using RMSE, a widely accepted metric for regression model performance, which measures the square root of the average squared difference between predicted and actual Ne. Mathematically, the RMSE is calculated as follows:

Results and Discussion

While Table II outlines the hyperparameters for the proposed model and the submodels, Bi-LSTM and AlexNet model, Table III represents the hyperparameters used for the ML models employed in our study. Table IV presents the RMSE and R

values, comparing the performance of previously introduced models

(ANN-TDD and ANN-IRI) with our proposed models (LSBoost, Bi-LSTM,

AlexNet, and ABRR-18), as well as the RO Ne data for the test set.

Specifically, the ANN-TDD model achieved an RMSE of

Notably, the LSBoost model outperformed the ANN-TDD and ANN-IRI models in terms of RMSE and R, with values of

Several factors may contribute to this disparity, including the complexity of ionospheric Ne prediction, which requires models capable of capturing intricate spatial and temporal patterns within the data. Traditional ANN models may struggle to learn and generalize effectively from such vast and complex datasets, potentially leading to suboptimal performance. In addition, while LSBoost is recognized as an efficient regression model, it may not sufficiently capture the nuanced relationships present in the data, especially given its reliance on decision trees, which may fail to address the complexity of the ionospheric Ne profile.

In contrast, advanced DL architectures could have the potential to effectively extract and utilize complex spatial–temporal features from the data, resulting in superior predictive performance. As a result, we applied DL models, searching for the best model that can perform efficiently on huge RO data through the F-layer. Also, to gauge the proposed model architecture, the model was compared against one of its components, Bi-LSTM, as previously stated. Furthermore, to justify the strategic choice of ResNet18, we developed a model using AlexNet instead of ResNet18, combined with the same Bi-LSTM and SAM. This comparison highlights the significance of ResNet18 in our architecture.

Through

these validations, we demonstrate the robustness and superiority of the

proposed model over its individual components and alternative

configurations. As previously stated, we applied Bi-LSTM as a sequential

algorithm, achieving RMSE and R values of

As evident in Fig. 4, there are some anomalous points resulting from the data selection technique. This technique involves choosing entire data profiles for specific days representing the equinoxes and solstices, enabling comprehensive testing of our model across full-day profiles.

A. Feature Importance

Understanding the importance of various features in predicting ionospheric Ne is crucial for the development and reliability of infrastructure projects that depend on satellite-based technologies. In this study, sensitivity analysis was utilized to provide a comprehensive understanding of the importance of each feature in predicting ionospheric Ne. Sensitivity analysis is a methodical approach used to determine how different input variables affect the output of a model.

The specific technique applied here involved the sequential removal of each feature and subsequently evaluating the model performance without it. By systematically omitting each feature, we can determine the contribution of each feature to the overall predictive accuracy of the model. More specifically, the performance of the model was first evaluated using all available features to set a baseline. Key performance metrics, such as RMSE, R, Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NS), Willmott index (WI), and relative absolute error (RAE), were recorded. Each feature was removed one at a time, and the model was retrained and reevaluated with the remaining features. This step was repeated for each feature.

The model performance measures without each feature were compared to the baseline performance. A significant increase in RMSE or RAE, or a fall in R, NS, or WI, demonstrates the importance of the eliminated feature. This sensitivity analysis technique provides a thorough understanding of how each feature affects model predictions, highlighting which features are key and which may be less essential. The sensitivity analysis results, shown in Table V, offer key insights into the significance of each feature in the model. The ranking column calculates the relative importance of each feature by comparing the model’s performance when the feature is omitted. The ranks reflect the order of significance, with Rank 1 being the most important feature and higher ranks indicating decreasing importance.

For the ARR18 model, the overall performance with all features included showed an RMSE of

The removal of Bz resulted in an RMSE of 1.0864, indicating that IMF variations moderately influence Ne predictions. While solar activity indicators are essential for capturing the ionospheric response to solar radiation, their removal increased RMSE to 1.1621 and 1.2375, respectively. The sensitivity analysis reveals that altitude, latitude, and longitude are the most critical features for accurately predicting ionospheric Ne. These spatial features capture the inherent geographic variability in the ionosphere. Temporal features such as the time of day and day are also significant, reflecting the dynamic nature of ionospheric conditions over time. In addition, space weather indicators, such as solar flux, provide essential information on the ionosphere’s response to solar and geomagnetic activity.

The sensitivity analysis highlights the most critical features for predicting ionospheric Ne, thereby allowing engineers to focus on these parameters when designing systems and protocols for remote sensing technologies.

B. Evaluation of RO Electron Density Data

The tested data are divided into disturbed and quiet geomagnetic storms based on whether Dst

RMSE and R for the test set under different geomagnetic conditions: (quiet, Dst

In addition, Fig. 6

represents the Bland-Altman plots of the test cases from RO

observations for the ABRR-18 model under quiet and disturbed geomagnetic

conditions, serving as another statistical method to validate model

performance. The mean difference (M.D.) is

Illustrates

a Bland-Altman plot showcasing the model’s performance across various

geomagnetic conditions in all test cases. The conditions are classified

as either “quiet” (Kp

In

both quiet and disturbed scenarios, the 95% confidence interval,

represented by (±1.96 SD), known as Bland-Altman interval, is [−0.20,

0.20]

The improvement in our model can be attributed to two main factors. First, the extensive temporal coverage of our dataset, spanning two full solar cycles and incorporating C-2 data, offers unparalleled spatial–temporal resolution compared to other missions. Second, the use of an advanced DL model, which integrates feature extraction through ResNet18 and a Bi-LSTM sequential algorithm, followed by a self-attention mechanism, significantly boosts performance. Despite that Yang and Fang [20] used the Ne data from IRI as prior knowledge and made corrections to the low ionosphere profiles by using IRI values and spline interpolation, the proposed model outperformed their model with only RO data.

To investigate the influence of solar activity on ABRR-18 model accuracy, years 2015 and 2019 were selected to represent periods of high and low solar activity, respectively. Then, the proposed model behavior was compared to the IRI-2016 empirical model, which has been widely used by many authorities in various applications [9], [31], [32]. The equinoxes and solstices occur on specific days of the year, driven by Earth’s axial tilt and its orbit around the Sun. For the years 2015 and 2019, we selected DOY 079, 172, 266, and 356 to represent these key seasonal events. To embark on, we test the RO-Ne profiles for the four days chosen with the IRI-Ne profiles in Fig. 7(b) and (d) through 2015 and 2019, respectively. It can be noticed that the consistency between them in a high solar year (R varies between 0.82 and 0.94) is higher than in a low solar year (R varies between 0.40 and 0.67), as shown in Fig. 7(b) and (d). The panels in Fig. 7(a) and (c) show that ABRR-18 accuracy is significantly higher in 2015, the solar maximum year, than in 2019, the solar minimum year, for the March, June, September, and December equinoxes, with R coefficients 0.95, 0.95, 0.95, and 0.93, and 0.85, 0.87, 0.73, and 0.87, respectively.

Linear regressions between the actual RO Ne, ABRR-18, and IRI-2016 during the solar maximum year (2015) shown in (a) and (b), and during the solar minimum year (2019) shown in (c) and (d).

Furthermore, ABRR-18 outperformed the IRI in both 2015 and 2019. In 2015, ABRR-18 yielded R of 0.95, 0.95, 0.95, and 0.93 compared to 0.93, 0.94, 0.82, and 0.86 obtained by IRI in DOY079, 172, 266, and 356, respectively. In 2019, as well, ABRR-18 dramatically prevailed over the IRI, with R values of 0.85, 0.87, 0.73, and 0.87, compared to 0.67, 0.40, 0.54, and 0.44 achieved by the IRI via DOY079, 172, 266, and 356, respectively. The correlation graphs also agree with the RMSE results, implying that the ABRR-18 model outperformed the IRI-2016 model in predicting Ne regardless of solar conditions.

C. Comparison With ISR Data at Jicamarca Station

Severe geomagnetic conditions typically have a significant effect on ionospheric Ne [33], [34], [35]. In quiet geomagnetic conditions, Ne profiles are regular and adhere to the Chapman function; however, in severe situations, ionospheric electron densities are considerably disrupted [19]. Predicting high-accuracy Ne profiles remains a significant difficulty for existing ionospheric models. As a result, the performance of the ABRR-18 model must be evaluated in both severe and regular geomagnetic conditions.

The present study uses the Ne profiles obtained from the Jicamarca ISR during two distinct geomagnetic storms: one during a severe geomagnetic storm on September 7 and 8, 2017, with a planetary K-index of maximum Kp = 8+, and the other during regular conditions on September 5 and 6, 2023, with a maximum Kp = 3. These values are chosen as the reference values, and a comparison is also made between the predicted profiles and both IRI-2016 and IRI-2020 models.

Fig. 8 compares hourly mean Ne profiles predicted by the ABRR-18 and IRI models to ground-based ISR profiles from midnight to sunset (00:00 to 18:00 LT) at Jicamarca (11.95°S, 76.87°W) on September 7 and 8, 2017. The RSME between model results and ISR data is displayed on each graph for comparison. The blue, green, red, and purple curves represent ISR, ABRR-18, IRI-2016, and IRI-2020 results, respectively. Overall, the mean profiles predicted by the proposed model are more compatible with Jicamarca ISR profiles than those of the IRI models during the studied hours, except for 15:00 and 18:00 LT during DOY 250, where the RMSE for the ABRR-18 model is larger than that for the IRI models, as indicated by the purple rectangle in Fig. 8(a).

Comparison of correlation (R) and RMSE between the ABRR-18 model (green), IRI-2016 model (red), and IRI-2020 model (purple) against ISR observations (blue) at Jicamarca (11.95°S, 76.87°W) during the geomagnetic storm on (a) September 7, 2017 and (b) September 8, 2017.

This indicates that our model outperforms the IRI models and some recent models, such as Yang’s model, which exhibited smaller RMSEs than the IRI-2016 at altitudes below hmF2 but performed worse at altitudes above hmF2, as noted by Yang and Fang [20]. In addition, during DOY 251, our model demonstrates superior performance compared to the IRI models, with notably low RMSEs, except at 13:00, 14:00, 17:00, and 18:00 LT, where our model surpasses the IRI-2016 but does not surpass the IRI-2020, as marked by the purple rectangles in Fig. 9(b). Furthermore, our model shows better performance in capturing altitudinal variations during many time periods, where the hmF2 values align more closely with ISR observations than those of the IRI models, as illustrated by the horizontal black and brown dotted lines in the third row of Fig. 8(b).

Same as Fig. 8 at Jicamarca (11.95∘S, 76.87∘W), but during quiet period on (a) September 5, 2023 and (b) September 6, 2023.

On the other hand, Fig. 9 presents a comparison of the mean ISR profiles at Jicamarca on September 5 and 6, 2023, during a quiet period in a year of high solar activity, with the mean Ne profiles predicted by the ABRR-18 and IRI models from 00:00 to 18:00 LT. The ISR observations, ABRR-18 results, IRI-2016, and IRI-2020 results are represented by the blue, green, red, and purple curves, respectively. As shown in Fig. 9, there is a strong resemblance between the mean Ne profiles predicted by ABRR-18 and IRI and the Jicamarca ISR profiles. Similar to the comparison between IRI and ISR observation, the RMSE between ABRR-18 predictions and ISR observations varies.

The ABRR-18 frequently performs better than the IRI-2016 and IRI-2020 models, except between 09:00 and 12:00 LT and 17:00 to 18:00 LT, where the RMSEs for the ABRR-18 are higher during DOY 248 in 2023, as indicated by the purple rectangles in Fig. 9(a). For DOY 249, 2023, the number of hours during which the RMSEs of the IRI models were lower than those of the ABRR-18 model increased, including 07:00 to 10:00 LT and 17:00 to 18:00 LT, particularly at altitudes above hmF2, as shown in the purple rectangles in Fig. 9(b). Furthermore, we notice an alternation in superiority between the IRI-2016 model and the IRI-2020 model, as the RMSE values indicate that this alternation occurs throughout the day and night without specific characteristics.

In conclusion, severe geomagnetic conditions tend to disturb ionospheric Ne, making accurate prediction difficult. Compared to ISR observations at Jicamarca, ABRR-18 demonstrates strong performance in estimating Ne, with results aligning more closely with ISR profiles than those of the IRI-2016 and IRI-2020 models, especially during severe storms on DOY 250 and 251 in 2017 compared to the quiet conditions on DOY 248 and 249 in 2023.

D. Model Evaluation for Capturing Global Ionospheric Spatial–Temporal Features

The ionosphere exhibits well-known worldwide spatial–temporal changes caused by solar ultraviolet irradiation; thus, it is essential to assess ABRR-18’s ability to capture these dynamic properties. As previously stated, the C-2 mission generates approximately 4000 profiles globally per day, indicating that they are well distributed geographically and temporally. The quality of these profiles has been evaluated in [36].

To

further assess the proposed model through the F-layer, we used 20-day

average Ne profiles from the C-2 mission around the March equinox in

2024 (March

Comparison of global ionospheric electron density maps in March 2024, noon (11:00–13:00 UT), for the ABRR-18, IRI-2016, IRI-2020 models, and COSMIC-2 profiles at (a)–(d) 200 km, (e)–(h) 300 km, and (i)–(l) 400 km. The white line represents the magnetic equator.

Comparison of global ionospheric electron density maps in March 2024, noon (11:00–13:00 UT), for the ABRR-18 model, IRI-2016, IRI-2020 models, and COSMIC-2 profiles. Each column represents the mean height for 50 km through the F-layer. The white line represents the magnetic equator.

The analysis of the global ionospheric Ne maps shown in Fig. 10 provides valuable insights into the performance of the proposed ABRR-18 model in capturing the spatial–temporal variations of the ionosphere, particularly during a severe geomagnetic storm in March 2024.

The COSMIC-2 (C-2) mission data, which serves as the ground truth, clearly demonstrate the strong dependence of ionospheric Ne on geographic and geomagnetic positions, as well as altitude. The high Ne levels observed in the Africa–India sector and the peak values at around 30°N and 20°S geographic latitudes align with our understanding of the ionospheric dynamics driven by solar radiation and geomagnetic activity.

When comparing the ABRR-18 model predictions to the C-2 data, the results are highly encouraging. The ABRR-18 model shows an exceptional ability to capture the spatial–temporal characteristics of the ionosphere, with mean correlation coefficients (R) of approximately 0.99, 0.958, and 0.90 at altitudes of 200, 300, and 400 km, respectively. This indicates a strong agreement between the model and the actual observations. The R values were computed to quantify the agreement between the observed Ne values from the C-2 mission and the modeled Ne values produced by ABRR-18, IRI-2016, and IRI-2020 at various altitudes. The values of R for each altitude are presented in Table VI. The analysis reveals that the ABRR-18 model outperforms both the IRI-2016 and IRI-2020 models at altitudes of 200 and 300 km, as confirmed in Fig. 10. However, at an altitude of 400 km, the IRI-2020 model exhibits better performance. Furthermore, it was observed that the IRI-2016 model surpasses the IRI-2020 model at lower altitudes (200 and 300 km) across various latitudes, as highlighted by the black dotted rectangles in Fig. 10(d) and (h).

While the ABRR-18 model slightly overestimates Ne at 200 km, with an R coefficient of 1.004, and at 300 km, with an R coefficient of 1.019, compared to IRI-2016, it demonstrates significantly better performance than the IRI-2020 model across the investigated altitudes with R coefficients of 1.6515 and 1.173 at 200 and 300 km, respectively, indicating a much larger overestimation compared to the IRI-2016 model. Notably, our findings align with those of Marew et al. [21], who reported that the IRI-2020 model tends to overestimate GPS-TEC with larger discrepancies during certain equinoxes and solstices. However, Marew et al. also highlighted that IRI-2020 performs slightly better in capturing positively enhanced GPS-TEC compared to IRI-2016. This is consistent with our results at 400 km, where the IRI-2020 model demonstrates greater robustness at higher altitudes, as TEC is typically calculated at altitudes exceeding 400 km. However, our analysis revealed that the IRI-2016 model is more effective at capturing Ne variations at low altitudes and latitudes, particularly during geomagnetic disturbances at noon times, as highlighted by the black dotted rectangles in Figs. 10 and 11.

Overall, the analysis of the global ionospheric Ne maps provides strong evidence that the ABRR-18 model is a promising tool for accurately predicting ionospheric conditions, especially during severe geomagnetic events. Its ability to align closely with the high-quality C-2 observations and outperform the widely used IRI models underscores the model’s potential for improving ionospheric monitoring and forecasting capabilities at low altitudes and latitudes.

Despite reducing the spacing between altitudes, there remains a strong consistency between anticipated Ne values using ABRR-18 and C-2 across all mean altitudes, ranging from 175 to 475 km, as indicated in the first two columns of Fig. 11. However, the IRI-2016 results indicate overestimation at low altitudes (up to 275 km) and underestimation at high altitudes (up to 475 km). Furthermore, the overestimation at low altitudes is concentrated in the Northern Hemisphere, as pointed out by the red dotted ellipses in Fig. 11, while the Southern Hemisphere is consistently underestimated at all altitudes. In addition, the IRI-2020 model shows underestimation at all altitudes compared to the C-2 observational data and our ABRR-18 model.

In contrast, the Ne maps generated by ABRR-18 and C-2 show a strong correlation across both hemispheres, except for a weaker correlation at higher altitudes, particularly in the western region, as indicated to the left of the red dotted lines in Fig. 11. In addition, the ABRR-18 model more effectively captures Ne disturbances in equatorial regions compared to the IRI models, especially IRI-2020, as highlighted by the black dotted rectangles in Figs. 10 and 11. It can be observed that the behavior in these equatorial regions through IRI-2020 gradually improves from west to east as the altitude increases.

Comparing the capabilities of IRI-2016 and IRI-2020 in capturing spatial–temporal characteristics against the ABRR-18 model with the C-2 observations during this disturbed period, we confirm that IRI-2016 outperforms IRI-2020 at low altitudes, while IRI-2020 shows better performance at higher altitudes (above 400 km).

Conclusion

Our work aims to use DL algorithms to construct an effective new 3-D ionospheric F-layer model. RO Ne profiles in the F-layer from different satellite missions, such as CHAMP, COSMIC1, FY-3 C, and C-2, are used to create the F-layer 3-D ionospheric model. The ABRR-18 model was successfully developed using an advanced architecture that integrates attention mechanisms with a recurrent ResNet18 framework. This innovative approach exploited ResNet18 for efficient feature extraction, the power of recurrent layers to capture temporal dependencies, and the attention mechanisms to highlight the most relevant features, ultimately ameliorating the model performance and accuracy. The data are divided into two sets: 80% for the training set and 20% for the test set, which includes four days per year that represent the equinoxes and solstices.

We assessed the performance of the ABRR-18 model against three ML models and two DL models on the test set under various geomagnetic conditions. Furthermore, ABRR-18 was evaluated during the equinoxes and solstices in 2015 and 2019, representing high and low solar activity years, respectively. Moreover, the performance of the ABRR-18 model was compared to entirely independent datasets from ISR at the Jicamarca station (11.95°S and 76.87°W) during both severe storm and quiet conditions, and it was validated against the IRI-2016 and IRI-2020 models. spatial–temporal characteristics were gauged during the March equinox of 2024 at noon at different altitudes. The key findings are as follows.

Ne predicted by ABRR-18 surpassed the results of several ML and DL models, including ANN-TDD, ANN-IRI, longstanding LSBoost, as well as Bi-LSTM and AlexNet.

In the test datasets, the ABRR-18 model achieved higher performance during severe geomagnetic conditions (Dst

<−20 ) than during relatively quiet geomagnetic conditions (Dst≥−20 ).The ABRR-18 model demonstrated superior performance during the year of high solar activity (2015) compared to the year of low solar activity (2019). It consistently outperformed the IRI-2016 model during these periods.

Regardless of geomagnetic conditions, the Ne profiles predicted by ABRR-18 closely align with ISR measurements. Except for a few instances throughout the day, ABRR-18 consistently surpassed the IRI-2016 and IRI-2020 models in terms of Ne.

Compared to both IRI models, ABRR-18 showed better performance in characterizing global ionospheric spatial–temporal features and demonstrated robust consistency with C-2 measurements at various low altitudes and latitudes through the F-layer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank COSMIC Data Analysis and Archive Center (CDAAC) GNSS Radio Occultation (RO) Datasets for providing CHAMP and COSMIC data via https://data.cosmic.ucar.edu/, FENGYUN Satellite Data Center for providing FY-3C data via http://data.nsmc.org.cn, and the International Reference Ionosphere (IRI) for providing the IRI-2016 model data via https://ccmc.gsfc.nasa.gov/. The numerical calculations have been done on a computer equipped with an Intel Corei7 CPU (3.20 GHz), 16 GB of RAM, and a GTX 1660 Ti GPU using MATLAB (2023a) and Python

No comments:

Post a Comment